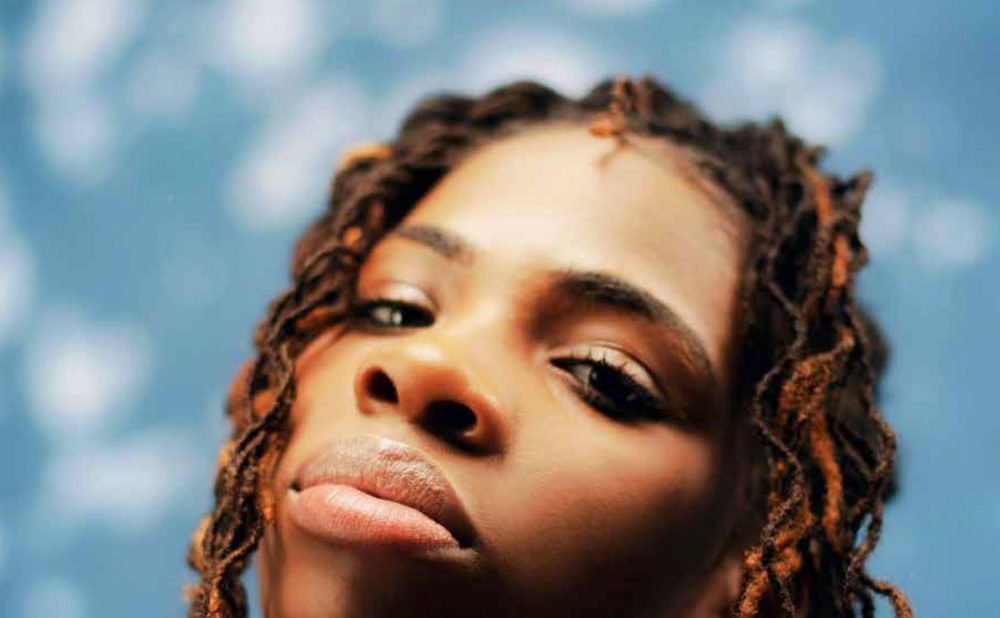

Mighty Good

The two-fisted power of Haviah Mighty’s soulful singing and superior rhymes should propel this rising Canadian rapper to worldwide wonders

2020 was supposed to be Haviah Mighty’s year. The Canadian rap superstar-in-waiting seemingly came out of nowhere—Brampton, Ont., actually—and became a performer that many, including Mighty herself, expect big things from. Still in her mid-20s, she’s already won growing audiences and the prestigious Polaris Prize, a critics’ poll that crowns the best Canadian album of the year, with searing rhymes and smooth, confident vocals. Her energized sound combines upbeat party tracks with challenging raps propelled by powerful beats. Despite, or perhaps because of, the sometimes-weighty issues raised on her songs—racism, misogyny, class—a Mighty show leaves an audience both exhausted and energized, in awe of a performer who never stops moving.

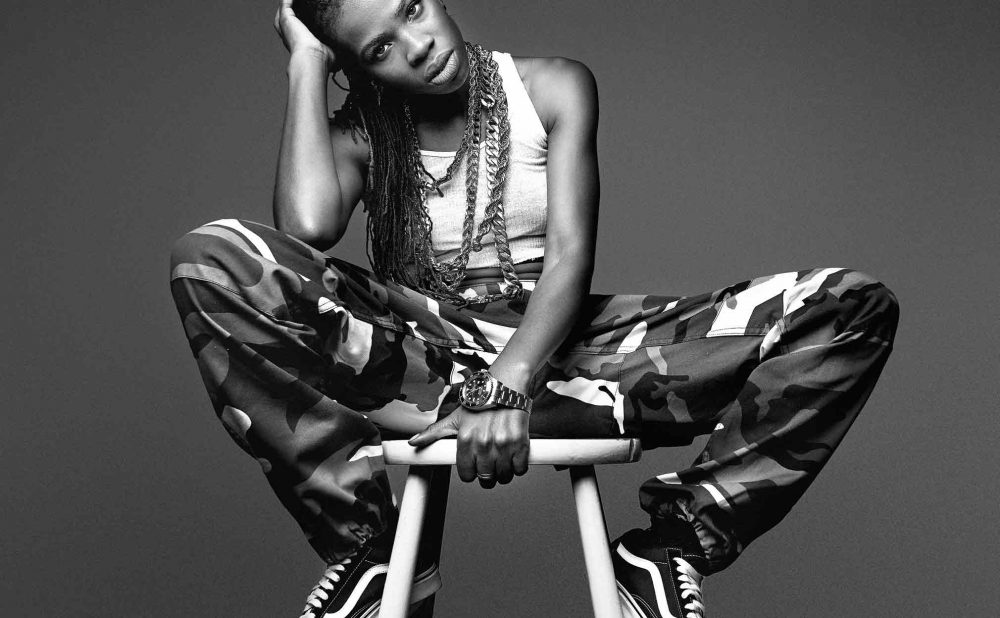

Mighty doesn’t just walk onto a stage, she seizes it. In front of a sold-out crowd or an empty room, Mighty grips the mic and an audience’s attention, prowling the stage, slightly crouched, ready for trouble but definitely not looking for it. With her elegant and essential best friend DJ Demone on the decks and guest appearances by stylish sister Omega, Mighty’s shows are an amped-up playground of passion and power.

It’s easier to tell yourself to roll with the punches when it’s happening to the entire world as well.

Mighty and her team were eager to unleash their talent on the world this spring. But in mid-March, as she readied to take a stage in Oakland—part of a tour that was supposed to introduce her to the U.S.—a text from a friend lit up her phone in the darkened club. The lights were slowly beginning to go out around the world.

“When I heard South by Southwest was cancelled, that’s when I knew it was over,” says Mighty, who was pumped to play her first gigs—four of them—at the legendary festival in Austin, Texas. “I was pretty certain if something that big was cancelled, everything was cancelled.”

Instead of wowing the States, Mighty holed up in her Brampton home when the virus hit, thinking, “If things fall apart, how will I sustain?” She had only committed to music full-time in 2019, after her Polaris win. For a few weeks, she went to a dark place. She wondered if she’d have to go back to a “regular” job to pay the bills—she used to be a clerk at Long and McQuade, where she taught herself how to DJ. “I started to feel a little down in the rut.”

But Mighty is remarkably upbeat about her lockdown time now. “It’s easier to tell yourself to roll with the punches when it’s happening to the entire world as well,” she says. “When I was condemned to the house, it allowed me to start making music. I had been starting to worry about how I’d write with all the touring planned.”

Mighty went deeply DIY, mastering Instagram Stories and learning the finer points of livestreaming from her house. She’s been more active than most online: in addition to her stepped-up social, she’s done more than 10 virtual shows, including, most recently, a sleekly produced stream for the Supercrawl Festival in Hamilton, Ont., where she previewed some new tracks.

Mighty’s productive homesteading has translated into two fresh singles: the powerful Atlantic, which evokes enslaved people’s ocean passage, followed by the more upbeat Occasion, slated for release in mid-December. Mighty is coy about the specifics of her new release, but as she prepares to follow up her hugely successful debut album, 13th Floor, it’s clear this forced “downtime” has been anything but. The two tracks ably showcase the performer’s strengths. Atlantic delivers searing commentary and evocative images pushed by powerful beats and scorching rhymes, while the newer track showcases Mighty’s singing skills, ones that she is quick to diminish.

“I’ve always considered myself a rapper who also sings,” she says. “People told me, ‘Your rapping is what’s going to get you somewhere, your singing won’t get you anywhere.’” But those smooth, rich, low-register tones between Mighty’s rhymes are just one of the many things that help set her apart from wannabe mic masters.

…..

Mighty has a ferocious work ethic, something she learned from childhood music lessons. Her parents and older sisters made sure she practised for classes they could barely afford. Eventually, the music school cut the Mighty family off from scholarships because they just kept winning them.

“I remember thinking, it’s not a choice, it’s what we do,” Mighty says of those lessons.

In addition to learning discipline, Mighty discovered how to breathe. “Unlike rappers who’ve never been taught to sing, I had a predisposition of understanding how to use my air, my diaphragm,” she says. As a result, she can drop more lyrics in one breath than other rappers who don’t know how to marshal the additional air. “The only thing missing musically for me as a kid was church,” she says, laughing.

Mighty also learned the sting of racism at an early age. She grew up in east Toronto in a neighbourhood of struggling working-class white families—as she puts it, “people who were deemed lower class who looked at a Black family and went, ‘Well, at least we’re better than them.’”

Her worried parents wouldn’t let their children out of the house, afraid for their safety. “We were the only Black family; we were targeted a lot,” says Mighty. “We had a brick thrown through our window, cops were called because our piano was too loud. Ridiculous stuff. When I lived in Toronto, what I looked like and the fact that I was Black said so much about me before I could say anything about myself.”

The close-knit and determined family wanted a way out. But when they began looking for a new home, real estate agents could not look beyond their race. “They kept trying to push us into racialized communities in Scarborough,” Mighty remembers. “My mom said, ‘Absolutely not, because I know this is where you put Black people who don’t have a lot of money.’”

The family eventually found agents who helped them get what they wanted, a new home in the diverse community of Brampton. “That changed all of our stories and all of our lives,” says Mighty. She would eventually name-check Brampton on her 2017 project, Flower City.

Humans can be a community for each other, but if we don’t know what’s going on in each other’s lives, we can’t support each other.

Before the move, Mighty was dubbed a “problem child” with “anger management” issues. She’s pretty sure that living under the grinding yoke of racism in Toronto had something to do with perceived attitude issues. When the family moved to Brampton, Mighty immediately excelled in school. She was quickly deemed a gifted student, a status she would hold through Grade 12.

“I felt like I was able to be a kid for the first time in eight years,” she says. “I didn’t feel so different anymore.”

When Mighty was 11, housing costs ate into the cash that paid for her music lessons, so she turned to rap to fill the musical gap in her life. She would race home from school, park herself at her computer and search for battle-rap opportunities online. She taught herself the craft by trading text and audio verses with American men two and three times her age on letsbeef.com. “I got my flow that way,” she says. “I was regularly in the Top 10 on the site—and I was the only woman.”

Mighty eventually graduated from online battle rapping to cypher events, where circles of rappers took turns freestyling over a never-ending beat. In 2016, Mighty participated in a Facebook Live cypher for women rappers and found her first bandmates, a quartet who would eventually be known as The Sorority. The group lasted almost three years before its members split up to pursue solo careers in 2019.

But during their run, the comparatively tiny Mighty regularly towered over her taller bandmates. It seemed clear at their shows that four MCs were a few too many for one centre-stage mic.

…..

As Mighty built her battle rap bonafides, her older sister called her out, claiming she was all style and no substance. She was admittedly adept at rhyming, but whose story was she telling? “My sister said to me, ‘You’re really good—but I don’t believe you.’”

Mighty became determined to develop her writing voice and drew on her life experiences, especially the pain of the early years, to find the stories she needed to tell. “I focused on becoming an authentic rapper, talking about things that resonated with me,” she says. “My ability to rap about race the way I do is because I am able to look at it from a reflective standpoint. This is how people I know and people who look like me feel. My ability to make the music I make comes out of escaping an environment but still identifying with the pain of that environment.”

Mighty writes with an intention to teach, educate and incite a dialogue, not to point fingers. “As long as conversations are happening, it’s a positive thing,” she says. “Humans can be a community for each other, but if we don’t know what’s going on in each other’s lives, we can’t support each other.”

Compact and powerful—and perhaps pugnacious—Mighty is now determined to be heard and seen in part because she felt invisible for much of her life. “When I was a kid, society’s message was that there were certain things that weren’t available for people like me. I didn’t fully believe I was worth the space I was taking up. That’s what I had to overcome with time, learning and realizing that people can see me.”

On a mild summer night in Toronto, months before the Polaris Prize win would change her life and COVID would change the world, Mighty is set to play an NXNE showcase of rap’s “future stars” that is unfortunately programmed against a Raptors game. A laptop and a pair of turntables sit on a stand in front of a quiet, sparsely filled room, the only buzz coming from TVs with the sound turned down. The few faces in the room are pointed at the screens, watching basketball.

Eventually, DJ DemOne emerges, sharply dressed as if for a dinner party or awards show. Still no heads turn to engage. Demone turns on the beats and Mighty bursts on stage in a vintage Raptors Dino T. Among the handful of people in the club, a few muster a show-me attitude, while the rest pay no attention at all. Unfazed, Mighty paces the tiny stage, eyes darting, beats building, making a plan, looking hungrily for eye contact—or an exit?

By the second track, Mighty leaps off the stage and into the scattered crowd. She bobs and weaves her way through the distracted and now-startled talkers like a flesh-and-blood pinball. She stops in front of one, then another, belting into a live mic millimetres away from them, not aggressively but needing to be heard. One after another, the audience members fall under the spell of this direct artistic intervention, peeling away from the game to crowd around the stage that Mighty commands for the rest of her short set.

“Listen to me, now,” she seems to say. “I guarantee it will be worth it.”