Moonage Daydream director seeks to re-invent the documentary

Brett Morgen seeks to create experiences rather than Wikipedia sessions

Moonage Daydream

Where: In theatres

What: Movie, 135 mins.

When: Now

Genre: Documentary

Why you should watch: Almost as strange and aspirational as David Bowie himself, this untraditional doc tries to reimagine the form with the result having more in common with a Bowie performance — or video — than a standard documentary.

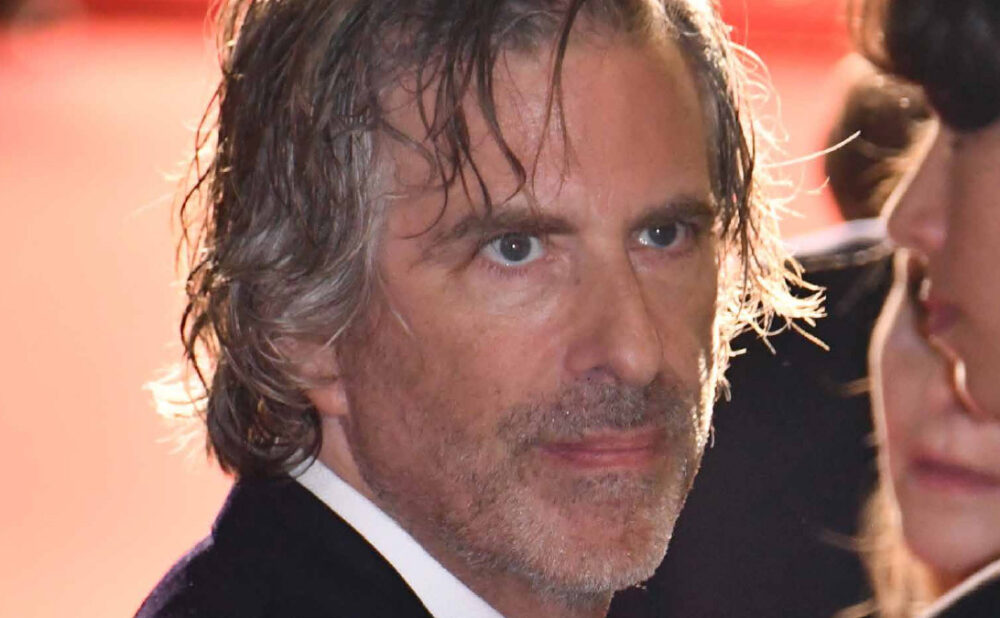

Ambitious Moonage Daydream director Brett Morgen is committed to re-inventing the documentary and his experiential, talking-head-free David Bowie doc is his latest effort in this quest.

The film is more like a Bowie concert — or one of his experimental videos, with little in common with traditional interview-driven docs.

Bowie’s is almost the only voice you hear throughout the film. And while Morgen had unprecedented access to thousands of hours of audio and video recordings (courtesy of the singer’s estate), he chose to use snippets rather than whole performances, opting to take us inside the performer’s mind rather than his resume.

“It’s not intended to be a documentary as we think of documentaries as information-based truth,” Morgen tells me as we meet in his Canadian distributor’s downtown Toronto office the day after Daydream’s TIFF premiere.

“This is an impressionistic film that I think arrives at a deeper truth than a fact-based film would.”

Morgen projects a visionary’s passion as he discusses a five-year film journey that saw the 47-year-old suffer a heart attack and the world enter a pandemic while he spent years reviewing archival material and working mostly alone.

And when he speaks of the qualities of his previous films, including The Kid Stays in the Picture and Cobain: Montage of Heck, they’re there in Moonage Daydream too and mark him as a filmmaker.

“I was making films that were fashioned in the stylings of the subjects I was depicting. They weren’t films about the subjects, they were films that were designed to personify the subjects. I didn’t use talking heads in any film for the first 20 years of my career.

“I tried to invite the audience to experience the past in the present tense. We aren’t talking about something that happened in my films— everything takes place in the present tense.

“When I started, that was not the case.”

Morgen continues, “When I make these films, I go all in.” And it’s easy to believe him as, even after a whirlwind of premieres and promo, he projects a laser (if somewhat beleaguered) focus and admits he originally had to be pressured to do press for the film. But he’s on the road, determined to help it succeed.

“With Moonage, I was like, what happens if we get rid of Wikipedia? What happens if you get rid of the facts and you get rid of the information? My subject matter is so iconic, I don’t need that story.

“Bowie really lent himself to this excursion because Bowie shouldn’t be defined. I’ve read every book about Bowie and they didn’t teach me anything, I didn’t get any closer to understanding his music or who he was as a person.”

“Bowie wasn’t putting his life on his sleeve; he was singing consonants and vowels half the time, but the more I listen to Bowie, the more I know about myself.

“This film is not going to be a resurrection, this cycle of life and this life-affirming message if I had not had that heart attack. I’m sitting there making a film about an artist whose stock and trade is being creative in periods of isolation and alienation — and that was an interesting bed fellow, an inspiring bed fellow.”

So why did he agree to do press after initially not wanting to overexplain the film or “to speak for Bowie”?

“I did realize that I had to get in front of the film to prepare people for the fact it’s not a biography — that was going to be the biggest marketing challenge for this film, to prepare people that it’s an experience, it’s a new genre. And to not come here expecting to hear about Lou Reed or Angie or his children or anything like that. That’s not this film.”

Morgen speaks of seminal LSD psychedelic experiences as a teenager —“not the micro dosing the kids use today” — tripping at Disneyland and Pink Floyd concerts.

“Probably one of the most exciting experiences of my movie life was seeing Willy Wonka when it came out — couldn’t have been more than two, three or four —and it was the colours and the neverland.

“I loved Fantasia as a kid, it was re-released when I was really young and though I didn’t say it at the time, my whole life, my whole career, I wanted to make Fantasia, something like Fantasia, which is a purely cinematic experience.”

And with the release of his nonlinear, impressionistic, experiential film, Morgen may indeed have achieved his unspoken wish.