Coal Mine Theatre’s ‘The Sound Inside’ is a wholly engrossing play about language

In Leora Morris’s masterful production of Adam’s Rapp’s acclaimed play, words are everything and nothing

What: The Sound Inside

Where: The Coal Mine Theatre, 2076 Danforth Ave.

When: Now, until Sun., May 28

Highlight: Moya O’Connell’s elegant navigation of her character’s tricky prose

Rating: NNNNN (out of 5)

Why you should go: It’s the quintessential Coal Mine show: great American play, excellent Canadian actors, cozy East End space.

“Bad poets make good playwrights,” wrote prolific American playwright and Yale creative writing professor Sarah Ruhl in her essential essay collection, 100 Essays I Don’t Have Time to Write. It’s an intriguing claim, and Coal Mine Theatre’s stellar new production of Adam Rapp’s acclaimed play, The Sound Inside, goes a long way toward proving it true.

The play — itself about a Yale creative writing professor, this one named Bella Baird (Moya O’Connell) — explores the difficulty of putting disaster into words. Attempting to make sense of their unfortunate circumstances, Rapp’s characters grasp, flailing, for metaphor. They’re full of bad poetry. And that’s a beautiful thing.

At first, Bella is the humble but comfortable narrator of her own story. In direct address, she proffers a comprehensive autobiography — age: 53; parents: dead; diet: high-fibre; hobby: book-collecting; cancer: somewhat advanced. If her illness leaves her feeling at all out of control, she does not show it.

But then it’s office hours and in barges brazen, Dostoevsky-devoted freshman Christopher Dunn (Aidan Correia) with no appointment, no winter jacket and no course-related question to ask (“I’m starting to get the feeling he just wants to hang out,” Bella observes, dumbfounded at his gall). Christopher is impulsive and combative, a foil to the reserved Bella, but the pair’s mutual loneliness and love of literature soon slings them into an intimate, boundary-breaking friendship. Eventually, Christopher gets so close to Bella’s heart that he too earns the power of direct address.

This is not a love story, though. Or, at least, not a conventional one. The two are bound together not by Eros but by Christopher’s in-progress novel, which Bella (herself an accomplished novelist, according to the Washington Post but not the New York Times) helps him with as he goes through the writing process. Focusing on Christopher’s novel helps Bella ignore her cancer, which for a time is pushed so thoroughly to the side as to be easily forgotten. But this fictional focus soon tightens to tunnel vision, and Christopher’s novel starts to intermesh with Bella’s life in increasingly disturbing ways.

Bella is a challenging role. A self-professed “creative writing hypocrite,” her text abounds in half-baked metaphors and affected literary asides. It would be easy for an actor to get caught up in the grandiloquence of the prose, but O’Connell avoids this trap. Whenever she can, she prioritizes action, psychologically justifying even the most idiosyncratic instances of Bella’s heightened language.

I’ll confess to spending most of the time Correia was on stage comparing him to Timothée Chalamet. Like Chalamet, he finds the truth underlying moments of cockiness; and Christopher, who hates email and school cafes with a passion, resembles Chalamet’s arrogant Lady Bird character, Kyle, in more ways than one. But ultimately, I concluded halfway through, Correia is more fiery and genuinely charismatic than Chalamet has ever been. It’s perfectly believable, I think, that Christopher would have the power to so thoroughly infect Bella’s mind.

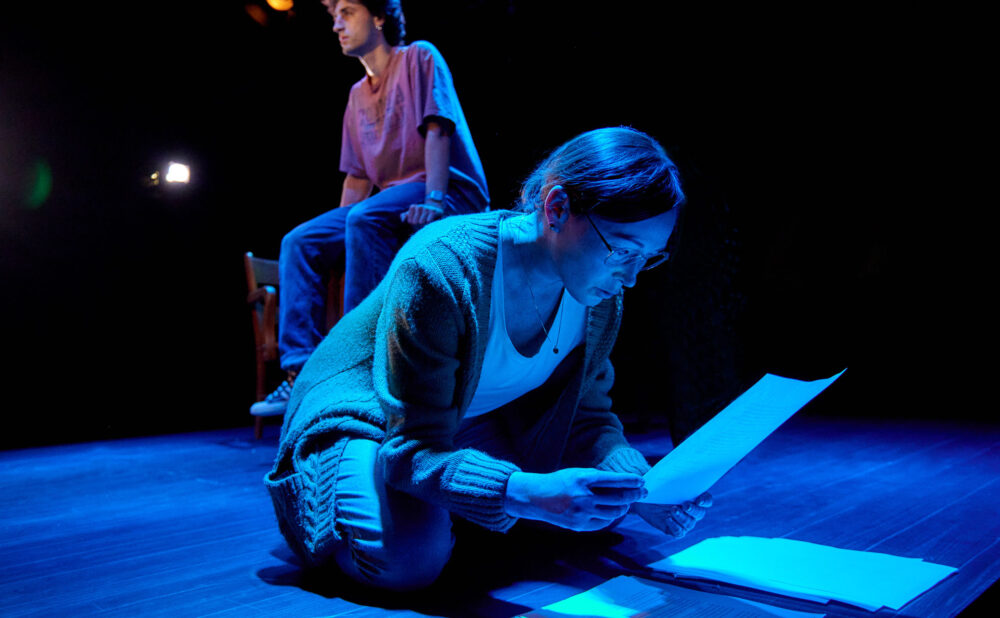

Bella tells her class that if an author does their “authorial job correctly,” not much description is needed: give a few details, and the “reader will create the rest of the character.” Such statements nearly demand that The Sound Inside have a fairly minimal design and director Leora Morris meets that challenge admirably, elegantly walking the tightrope of giving the play’s world enough detail to make things specific but not enough to limit the audience’s imagination. Wes Babcock’s set features an endearingly clunky wooden desk but is otherwise fairly empty, and a chasmic darkness (he also lit the show, which is done in proscenium) surrounds the stage at all times. Laura Delchiaro’s costumes are, by contrast, ultra-specific, with Bella’s green knee-length cardigan and Christopher’s cozy woollen socks putting us exactly where we need to be. And Chris Ross-Ewart’s sound design underscores the show’s climax with a cinematic, nearly Pixar-esque composition that might be cheesy if it weren’t so totally, gut-wrenchingly earned.

I have questions about the pacing of Rapp’s script — it’s too perfect and its production-line efficiency too uncomfortably American. But Morris’s compassionate directorial hand finds the delicacy between the piece’s well-oiled iron gears; the quiet within the racket.

The Sound Inside is the quintessential Coal Mine show: great American play, excellent Canadian actors, cosy East End space. It’s haunting, masterful, and, yes, inevitable.