Eagerly anticipated Oppenheimer underwhelms while overwhelming

Christopher Nolan’s latest doesn’t deliver characteristic visual bang

Oppenheimer

Where: In theatres

What: Movie, 180 mins.

When: Fri., June 21

Genre: Drama

Rating: NNN (out of 5)

Why you should watch: Christopher Nolan’s highly anticipated biopic of J. Robert Oppenheimer and the atom bomb is a complex, if underwhelming, historical saga.

WITH HIS LATEST FILM, Christopher Nolan is tackling the most complex and controversial subject of his career, but the visceral impact of the atomic bomb gets lost in the film’s own concern with historical significance. With Oppenheimer, Nolan has the task of condensing his considerable source material (the film is based on American Prometheus, a 700-page biography of Oppenheimer) into a comprehensible plot, but he also has to turn theoretical physics — and the men in suits who toil over them — into compelling imagery. The action of Oppenheimer is intercut with flashes of troubling images: sparks of orange light, squiggly blue lines (like the streak inside a marble) and a wave of fire crawling across a black sphere. These abstractions of matter against a black background are like intrusive thoughts, reflections of Oppenheimer’s creeping guilt and horror.

But these flashes are used so frequently and insistently in the first part of the film, punctuating the story like unnecessary commas, that when we finally do get to see the bomb in its awful glory at the Trinity test, it’s a little anticlimactic. Nolan, who gave us awe-inspiring set pieces in Inception (2010), Interstellar (2014) and Tenet (2020), is exactly the right director to wield cinema’s sights and sounds to transmit the impact of the blast. But most of the film involves men talking in laboratories and board rooms, and even the frenetic editing style (that intercuts scenes from different times and places in the plot) can’t quite maintain momentum throughout the three-hour runtime.

The central concern of the film is Oppenheimer’s moral quandary. When trying to explain quantum mechanics to his student at UC Berkeley, Oppenheimer describes an element that is in two different states at once. “That’s impossible,” the student replies. It is theoretically impossible, but as Oppenheimer explains, it is also true. At the heart of Nolan’s film is also a truth that feels impossible to believe: that the scientists responsible for inventing the atomic bomb, under Oppenheimer’s charismatic leadership, did not grasp the magnitude of what they were unleashing on the world. Only after Oppenheimer hears that the bomb has hit Hiroshima does he contend with the actuality behind the theory, but it remains unclear how or if he really could be that naive.

The gravity of his invention is made terribly real in a remarkable scene that takes place after news of Hiroshima has reached Los Alamos (the top-secret research centre Oppenheimer ordered to be built in the desert) when Oppenheimer gives a speech to an overly excited crowd. As the gravity of the bombing dawns on him, he hears the cheering crowd go silent except for one panicked scream, and soon the happy audience is bathed in a flash of white light, their skin peeling and turning black. It’s a testament to what Nolan can accomplish when he uses his considerable skill towards a visceral impact, and it may be one of the most striking scenes of his career. But when the same effect is used at the end of the film, when Oppenheimer is being questioned in a boardroom, the impact falls flat.

The last section of the film is devoted to Oppenheimer’s battle with the U.S. government, which was initiated by his speaking publicly on the danger of a nuclear arms race, anti-Communist fervour (Oppenheimer had dabbled in leftist politics and his wife was once a member) and animosity between him and Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.), a politician and businessman who was a member of the Atomic Energy Commission. Strauss initiates a hearing over the renewal of Oppenheimer’s security clearance (the loss of which would effectively end his career), in which his professional and personal life is picked apart. While the hearing provides a useful framing device for the plot of the film (the action is told in flashbacks), it becomes the dramatic centre of the film’s climax, which is somewhat underwhelming considering it involves not the fate of the world or the impact of the bomb but two men’s professional reputation.

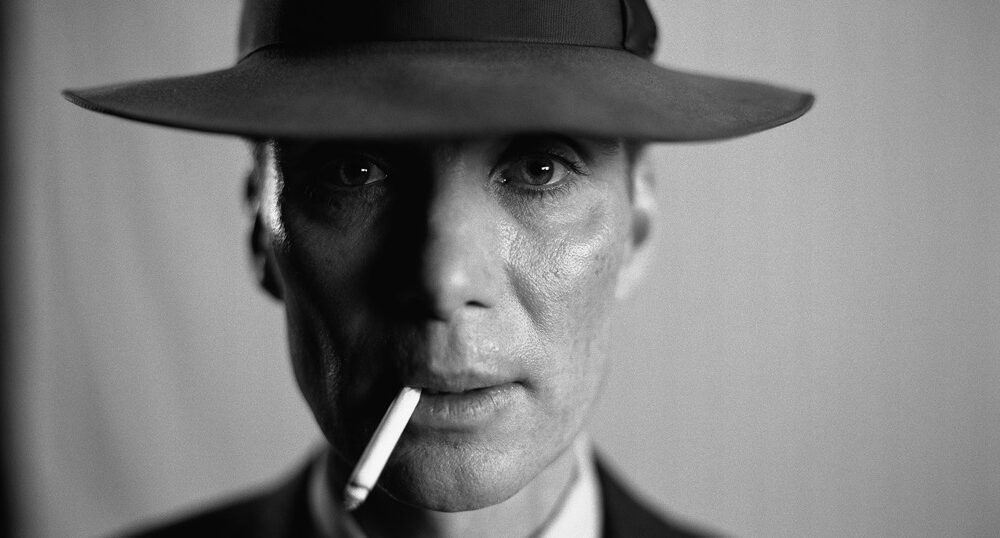

Whereas Nolan’s films are always technically impressive, they have a tendency to be emotionally distant. But Oppenheimer is not cold, due in large part to Murphy’s performance, whose face bears the weight of the shame, awe, wry humour and ultimate defeat of a man who altered the course of the world. And Emily Blunt is powerful as Oppenheimer’s troubled wife, Kitty, but the film disappointingly (or predictably, considering Nolan’s track record with female characters) does little with her story, never investigating the source of her depressive episodes and alcoholism. Nolan also seems to be responding to criticism that his films are devoid of eroticism by including two very brief sex scenes that are about as passionate and believable as you’d expect from the director (i.e. not at all).

In an interview with Variety, Nolan claims that viewers have been leaving the film feeling devastated and emotionally wrecked. But while the film covers a lot of historical and biographical ground, it doesn’t deliver enough of an emotional or sensorial blow. Oppenheimer is by no means a dud, but when the last image cuts to black, it feels a bit more like a whimper than a bang.