‘King Gilgamesh & the Man of the Wild’ is a heartful blend of old and new

Soulpepper Theatre’s production of the Toronto-set show features complex music by Moneka Arabic Jazz

What: King Gilgamesh & the Man of the Wild

Where: Soulpepper Theatre, 50 Tank House Lane (Distillery District)

When: Now, until Aug 6

Highlight: Moneka Arabic Jazz’s genre-crossing music

Rating: NNNN (out of 5)

Why you should go: The playful but polished show is a community-lifting comfort; it blazes like a campfire piercing a sea of darkness.

THIS SUMMER, Toronto theatres are singing old songs from way back when. The blockbuster opening of the season was Mirvish’s Hadestown, Anaïs Mitchell’s hit Greek mythology musical. And the Toronto Fringe played host to CAEZUS, a hip-hop concert adaptation of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar.

Soulpepper and TRIA Theatre’s King Gilgamesh & the Man of the Wild, in Toronto after premiering at this year’s Under the Radar Festival in New York City, delves into a tale older than both Greeks and Romans: the Mesooatamian Epic of Gilgamesh, well-known for being the oldest extant written story. The playful but polished show is a community-lifting comfort; it blazes like a campfire piercing a sea of darkness.

The music-theatre two-hander alternates its telling of Gilgamesh with scenes tracing the arc of a contemporary friendship. In a Toronto coffee shop, owner Ahmed (Ahmed Moneka) meets customer Jesse (Jesse LaVercombe — yes, these characters are semi-autobiographical). The two overcome Canadian shyness and connect despite their very different, though occasionally intersecting, backgrounds: Ahmed is an Iraqi artist barred from his birth country because he played a queer character on screen; Jesse is a struggling Minnesotan actor preparing for a minuscule role in an upcoming Hollywood military picture.

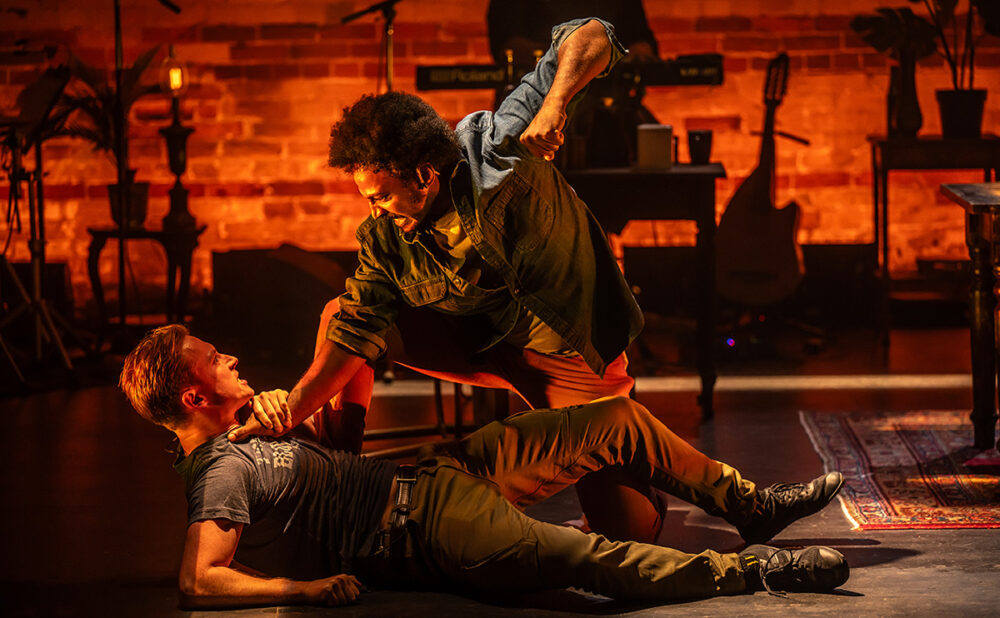

Ahmed mentions Gilgamesh, assuming Jesse knows it. He doesn’t, so Ahmed launches into recounting the story, which turns out to have parallels to Jesse’s life. The epic’s fragmented plot — which involves a king named Gilgamesh befriending Enkidu, the titular man of the wild, and going on a journey — is mostly unimportant to the show; what matters is the physical re-enactment of it. At near-random moments, Moneka and LaVercombe transform into King Gilgamesh and Enkidu respectively; to make clear that they are now new characters, they pivot from a realistic acting vocabulary to a heightened, somewhat declamatory one. They tell a chunk of the story, then snap back to their contemporary selves.

Director Seth Bockley (who wrote the show with Moneka and LaVercombe) uses design to differentiate the two settings. Lorenzo Savoini’s vibrant lighting becomes darker and more overtly theatrical for the Gilgamesh scenes, with the biggest change being a boxing ring-like rectangle of light on the floor. His rustic cafe set — a large carpet, third-wave coffee equipment, plants and a wooden table with chairs — doesn’t change much, though on-stage lanterns and chandeliers contribute to the shifting lighting design.

But the music, carefully balanced by Adrian Shepherd Gawinski, is the show’s selling point. Moneka’s six-piece band, Moneka Arabic Jazz, lines the stage and punctuates the story with complex harmonies and grooves. Moneka sings, Max Senitt drums, Jessica Deutsch plays the violin and Waleed Abdulhamid plays bass; the other two, woodwinder Selcuk Suna and bandleader Demetrios Petsalakis, play more than one instrument. The band’s sound is jazz and blues forward, with Afro-Arabic influences pulled in from Moneka’s background and the diverse Toronto music scene. Their unique approach would be a treat anywhere but feels especially revelatory on stage, considering how generic — and white — much musical theatre still is.

Overall, the show is an absolute treat and seems to be a crowd-pleaser. Though what it does with the Gilgamesh myth isn’t exactly challenging, it is deeply felt, crystal clear and consistently entertaining.