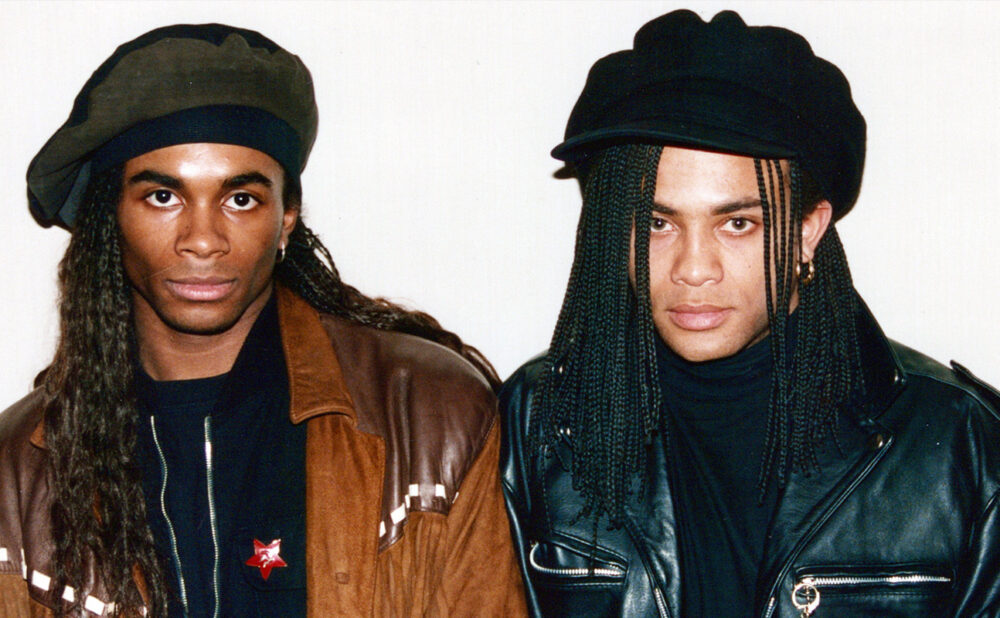

Milli Vanilli star admits to lies and abiding love of music

Singer at centre of one of industry’s biggest scandals tells all in new film

Milli Vanilli

Where: Paramount+

What: Movie, 106 mins.

When: Now

Genre: Documentary

Rating: NNNN (out of 5)

Why you should watch: Surprisingly honest depiction of one of greatest scams in music history. It’s the story of how a couple of broke DJ/dancers became Milli Vanilli and tricked the world — for a while — into giving them superstar status and a Grammy they had to return. All for performing songs they didn’t sing. Riveting, revealing and ultimately sympathetic to the band.

TALKING ON ZOOM from his home in Europe, Fabrice “Fab” Morvan, still has hints of the star power — as well as the good looks — that helped him and his bandmate, Rob Pilatus, become the world-beating late-’80s music sensation Milli Vanilli. The band came crashing to Earth even faster than their meteoric rise, which took them to the top before they were exposed as fraudsters who did not record their songs.

But damn they were good songs.

Girl You Know It’s True?

An awesome track and perhaps the most ironically titled song ever — sorry Alanis — and didn’t Morvan and his partner look superb miming along with the mega-hit on legendary videos and at shows?

It was a great ride for Morvan and Pilatus — until it wasn’t. The two formerly homeless wannabees were briefly on top of the world and all they had to do was make a deal with the devil.

That “devil” would be Svengali-esque producer Frank Farian, who had previous success “creating” Boney M and who tossed Milli Vanilli under the bus once the scheme started to unravel at a hastily called press conference in November 1990, after the boys had won a Best New Artist Grammy under a wall of suspicion.

And the deal only incrementally became clear after the two had signed a binding contract with Farian without really reading it. In a truly masterful act of spin, Farian and all the executives who went along with the deal, including music legend Clive Davis, managed to leave all the blame for the Vanilli con squarely on the band.

The fallout eventually killed Pilatus while a devastated Morvan finally got his life back on track.

“It took a lot of energy to come to this point, to be as positive as I am today,” says the charming and engaging Morvan, his latent star power charisma still evident.

“When I fell hard emotionally, spiritually, I was full of scars. And it took me years to heal all the scars.”

The level of anger towards the band after their scheme was outed was stunning: from the standard burning of albums and CDs to civil lawsuits demanding restitution for fraud, death threats against them and their family and shunning by the industry. Even strangers on the street would shout abuse at them.

“I was so disillusioned by the fact that we were let down, that nobody took our side, that we were scapegoats.

“That’s weird because there were record companies, there were major figures involved, like Clive Davis and Frank Farian, but for some reason, they were both not investigated properly.

“It seemed like the journalists gave up on investigating them. Why? Because people didn’t want to ruffle feathers. But you know what? We need to find a scapegoat so let’s go for Rob and Fab, they are the ones responsible for everything that happened; let’s go for that.

“And then the narrative started and ended up just like that at the end. We were blacklisted, Rob lost his life. We were almost like lepers. Even if we wanted to start something else, people were like ‘Oh no, we can’t get involved with those two.’”

In conversation and in the film, Morvan makes no attempt to run from responsibility and admits, “We lied.” He’s happy the filmmakers probed and went deep into the story.

“I knew they’d ask hard questions of everyone, me included. I wanted the hard questions; I didn’t want to scratch the surface. I wanted to go deep because I’m at fault too, I lied. I embraced it — until I couldn’t embrace it.”

He explains he and Pilatus were broke, living in overwhelmingly white Munich and desperate to make it big when Farian spotted them dancing on a German hit parade show on TV. The naïve pair were eager to believe anything that seemed to promise a career in show business. and Farian’s Boney M credentials just made his claims more plausible.

They quickly signed a contract without reading it and it was only after Farian tantalizingly played them bed tracks for Girl You Know It’s True did he let them know they wouldn’t actually be singing on the album.

“We were furious,” Morvan says in the film. But after already having a taste of the good life of photoshoots, fancy cars and fawning attention, the duo decided to suck it up, convinced they would eventually be able to sing on their tracks.

We learn in the film this was never a possibility from the producer’s point of view.

Both singers had spent time living in their cars before stardom was offered to them and the life put in front of them appeared to promise everything they dreamed of — except actually singing their tunes.

“The love that we didn’t receive at home, in our respective homes — Rob being an orphan and my parents being divorced — pop music really supplied that love. Oh, my god, it was so much love that it was almost overwhelming,” says Morvan, his face lighting up as it often does when we talk, despite his recalling ultimately tough times.

“But when that love disappeared in one day, woo hoo, that was tough. Suddenly, I realized that it was not real. When you’re into it you feel like, ’Okay, they really love me for myself.’ But no, it stopped.”

The almost violent response to the unmasking of Milli Vanilli seems even stranger today when so many artists perform much of their shows to tracks. People took it personally, demanding an “authenticity” that seems no longer required as long as the show is great.

Does he think race had anything to do with the backlash?

“No, I don’t like to play the race card but, okay, I will say, where there’s smoke, there’s fire.”

He later learned that the NAACP had started to investigate what happened to the band but abandoned the case when they returned to Europe.

“They were coming with attorneys to look into the story, would have been very different to have attorneys look into it. But I didn’t have the money to; I was trying to protect myself from all those class actions that were put in by attorneys with ads in newspapers with 1-800 numbers: call this number if you want to go into a lawsuit against Milli Vanilli. It was so orchestrated.”

Morvan says his love of music sustained him and his belief that, eventually, he would find his way back to singing and performing.

“I always wanted to sing, and I kept working on myself. I made a mistake, but I’m not bad after all, let’s keep going. I didn’t know where the journey would take me, but I knew music was calling and nothing, nothing else. I don’t have a Plan B; Plan A, let’s go.”

Morvan says new music is coming, he performs regularly and, yes, he sings Milli Vanilli songs.

“Yeah, yeah, the Milli songs are great, man. Milli Vanilli, Rob and Fab, we can never be disassociated. They’re connected forever, for life, we can’t separate them.

“The music turned me into what I am today, painful but also joyful. Life gave me music as a creative. When I create, I come from a different place. I’ve experienced this rainbow of emotions you’re supposed to use when you write.

“You have those emotions and I think being vulnerable as an artist is a wonderful asset. When I create, I am vulnerable so when people listen, they are going to feel something.

“Music is the best, the best thing, my best friend for life.”

And despite a near-fatal relationship with the music industry, when the passionate Morvan declares his abiding love for music and making it, you believe him when he says it — no bullshit this time.