Review: Aluna Theatre’s ‘On the Other Side of the Sea’ swims in engrossing ambiguity

Soheil Parsa directs absurd work by Salvadoran playwright Jorgelina Cerritos

What: On the Other Side of the Sea

Where: The Theatre Centre, 1115 Queen St. W.

When: Now, until Sun., Feb. 25

Highlight: Beatriz Pizano’s tender performance as civil servant Dorotea

Rating: NNN (out of 5)

Why you should go: Canadian premiere production offers rare chance to see Jorgelina Cerritos’s complex work performed.

HOW LONG do you have to live by the ocean before the endless crashing of waves becomes routine? And, when it does, do you welcome the sound into your life’s daily rhythm or segregate it to the background?

Salvadoran playwright Jorgelina Cerritos’s On the Other Side of the Sea latches onto the existential undertones of such questions. The absurd play imagines the seaside as a liminal space, a border between past and present where the rules of ordinary life come apart. Aluna Theatre’s Soheil Parsa-directed Canadian premiere production at The Theatre Centre demonstrates the literary power of Cerritos’s script (here translated by Dr. Margaret Stanton and Anna Donko); it made me want to dive into her complete works. But the production itself is less perfectly wrought, at times struggling to produce enough momentum to make the static dramatic situation interesting.

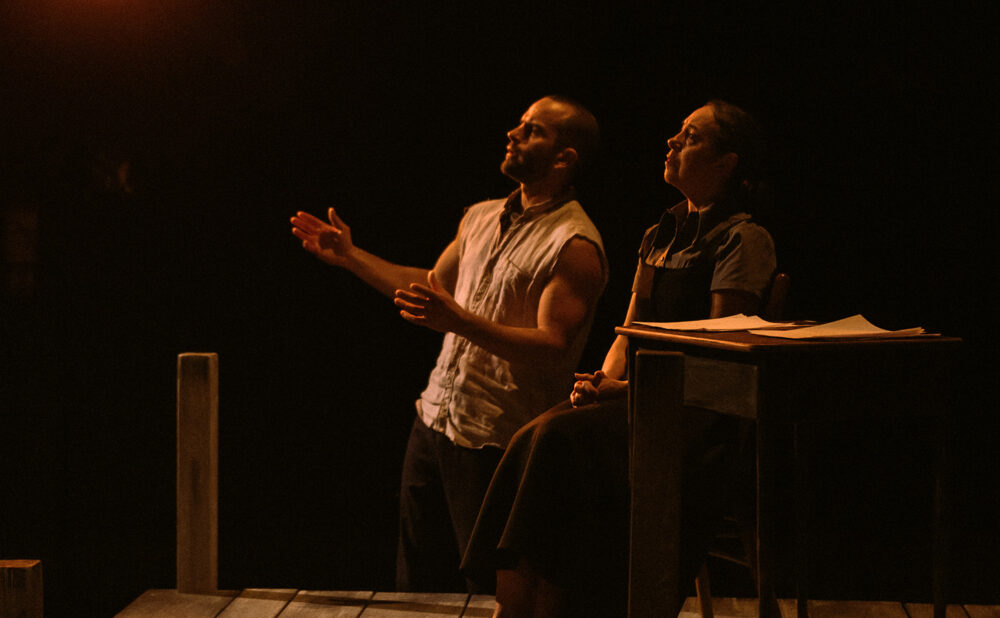

A stern middle-aged woman named Dorotea (Beatriz Pizano) anchors the 80-minute two-hander. A civil servant, she creates birth certificates for a living. It’s dull work, though it requires concentration — a difficult state to come by, since she works on a dock attached to a beach (designed by Trevor Schwellnus): distractions abound.

The loudest of which comes in the form of an extroverted fisherman (Carlos Gonzalez-Vio). Currently undocumented, he badly needs a birth certificate so he can participate in society. That might be doable if he knew who his parents were. Or his birth date. Or his name.

It’s a case of an unstoppable force taking on an immovable object. The fisherman makes up his mind that he won’t leave the dock without documentation, but Dorotea has no way of giving him what he wants. He navigates the space with playful lightness as she remains glued to her desk.

The performers work in contrasting registers. Pizano is down to earth, carving out Dorotea with flicks of the eye and deep breaths. Though restrained at first, emotion eventually waterfalls forth: a heartbreaking arc. Gonzalez-Vio plays broader. Text is his primary vehicle of characterization. While Pizano’s attention to nuance contrasts the script’s absurdity, Gonzalez-Vio underlines the comedy in Sharpie. These opposing approaches make a degree of sense — the characters are from different worlds, after all — but lend the two-person scenes a choppy, inconsistent quality.

During monologues, however, the production comes to life. It helps that they’re the play’s most enticing passages — floods of language detailing the characters’ mysterious pasts that bubble up from almost nowhere. Schwellnus seizes upon their inherent theatricality, isolating the person speaking in warm side lighting.

Theatre nerds will delight in this rare chance to see Cerritos’s work performed. Enigmatic complexity crashes on the play’s every shore. Aluna Theatre’s production lets us in on this magic without adding much to it.