Review: ‘As I Must Live It’ envelops Theatre Passe Muraille in wordplay and heart

Autobiographical Luke Reece solo show features youthful design

What: As I Must Live It

Where: Theatre Passe Muraille, 16 Ryerson Ave.

When: Now, until Sat., March 2

Highlight: Luke Reece’s rhyme-scattered script

Rating: NNN (out of 5)

Why you should go: Reece mixes theatre and spoken word in highly personal world premiere.

THE AUDIENCE has gathered in the lobby for an 8 p.m. play. At the stated hour, the theatre doors remain closed. But then, from the stairs leading to the floor above, a backpacked man hurries forth. With the crowd still standing, the doors still shut, he speaks, beginning the play.

So progresses the delightfully scrappy opening of Luke Reece’s new solo show As I Must Live It, playing at Theatre Passe Muraille in a co-production with Modern Times Stage Company. After Reece’s short lobby speech, he ushers the audience into the theatre, where the rest of the 90-minute show unfolds. Similarly unexpected audience interaction appears throughout director Daniele Bartolini’s staging, to mixed results.

The autobiographical show is highly personal, covering a wide range of territory before eventually homing in on Reece’s relationship with his father, who fell into a deep depression after losing his job when his son was 10. Much of Reece’s writing has grappled with this occurrence, we’re told, from a Grade 12 essay that received an A to a spoken-word piece called “Creases,” which Reece has performed across the city.

In addition to being a theatre artist, Reece is a decorated slam poet (he won the Toronto Poetry Slam in 2017). Those chops are given a light but effective workout in As I Must Live It, which walks the line between theatrical monologue and poem. The rhyme-scattered, rhythmically complex script is the piece’s sharpest point.

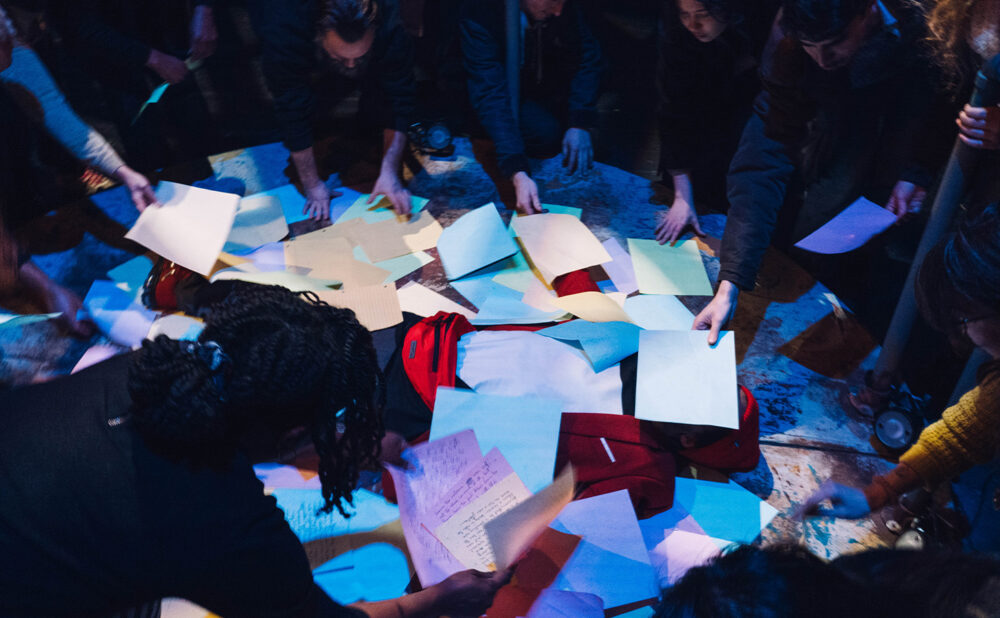

Reece begins his story in kindergarten, informing the production’s visuals. Jackie Chau’s in-the-round set, a circular platform that splits into different wheeled sections, is littered with pieces of colourful paper fit for an elementary school classroom. Projections by Barret Hodgson and Thom Buttery add a dash of visual interest. And Reece’s performance is frequently cheery, to the point that I wondered whether the show is aimed partially at children.

Yet there’s something oddly frantic about the production. Bartolini has layered in a great deal of audience participation: the constantly moving Reece has spectators hold some of the show’s props, for instance; and there’s a moment where the crowd must trade around sheets of paper to better understand a key story point. But I find myself struggling to see how much of this action relates to the script.

Reece’s story is interesting enough without all the extra icing — to lather the cake in it betrays a degree of insecurity and obscures the original taste. Sequences in which Reece shares his story without excessive flourish are, instead, the most resonant. When As I Must Live It stops fighting to please, it pierces.