Review: The simplicity of Lepage and Côté’s ‘Hamlet’ ballet disarms

Acclaimed duo brings wordless take on Shakespeare to Elgin Theatre

What: The Tragedy of Hamlet: Prince of Denmark

Where: Elgin Theatre, 189 Yonge St.

When: Now, until Sun., April 7

Highlight: A haunting choreographic depiction of Ophelia’s drowning

Rating: NNNN (out of 5)

Why you should go: Director Robert Lepage and dancer-choreographer Guillaume Côté’s confident, clear-as-glass execution.

WHEN YOU HEAR that two of Canada’s most talked-about stage artists, director Robert Lepage and dancer-choreographer Guillaume Côté, are premiering a ballet called The Tragedy of Hamlet: Prince of Denmark at the large Elgin Theatre, you’d be forgiven for thinking it would involve complex stage technology and towering design (especially if you saw the pair’s ethereal Frame by Frame at the National Ballet). Or that it would deconstruct Shakespeare’s play with aggression, producing a result ambiguous, even unrecognizable.

Instead, the simplicity of the 100-minute piece is what disarms. At least to my eye, it’s unlikely that the goals driving this Hamlet ballet are much different from the many other adaptations in existence. The confident, clear-as-glass execution — not the broader concept — provides the show with its unique power. (The ballet is presented by Show One Productions and produced by Ex Machina, Côté Danse and Dvoretsky Productions.)

Côté and Lepage’s design features many artificial candles held by candelabras and chandeliers (lighting is by Simon Rossiter). These on-stage light sources help reproduce the shadowy look a castle in the late Middle Ages would’ve had. The atmosphere is a good deal more realistic to the period than stage productions tend to be — the necessarily figurative nature of Côté’s choreography rubs up against this verisimilitude, generating productive friction. A screen of the sort generally used for surtitles also hangs above the action. Its primary purpose is to clarify things via stage directions (“Enter HORATIO,” etc.), although it dabbles in anagramming lines from the script (“Words, words, words,” becomes “Sword, sword, sword”). The plot, meanwhile, is more or less faithful to Shakespeare.

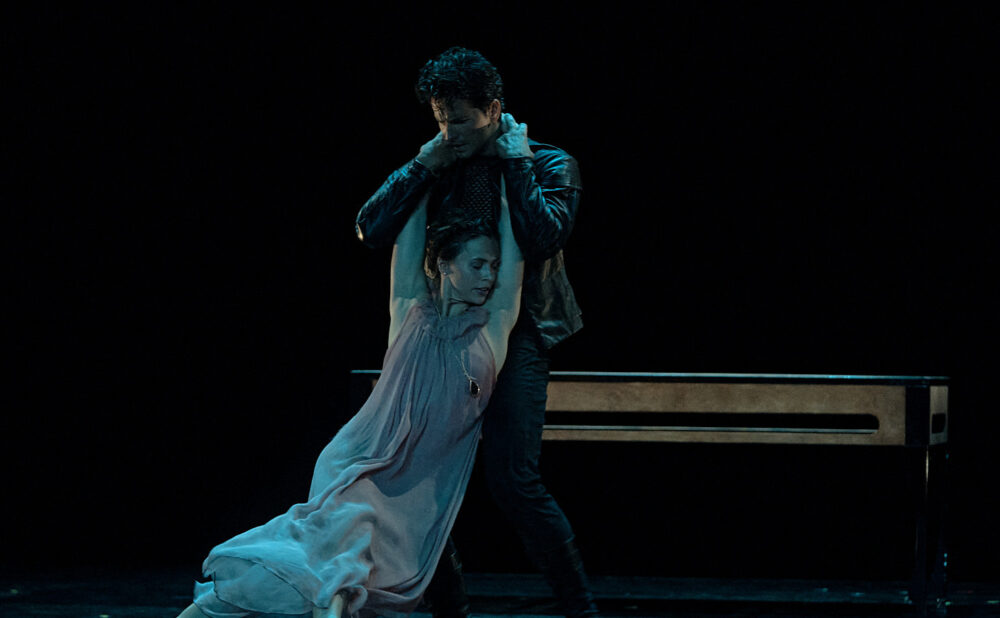

The choice to use the play’s full title — not just Hamlet — resonates: this is a particularly tragic take, one that emphasizes the many lives our title character (danced by Côté) tears asunder in his quest for revenge against Cladius (Robert Glumbek). From the beginning, Côté’s Hamlet is a violent one; in a moment replacing the “To be or not to be” speech, he twirls around with a rapier, repeatedly slashing the air, before hovering the blade over his wrist: a session of fencing, a skill Hamlet later employs to murder others, almost turns into a session of self-harm. The muscular Côté is terrifying as he bounds through the air: has Hamlet ever been so athletic, so capable of destroying everything in his path?

But there’s something equalizing about the ballet form. The character of Hamlet has the most lines of any Shakespeare character, triple Cladius and almost 10 times more than both Ophelia (Carleen Zouboules) and Gertrude (Greta Hodgkinson). But through dance solos — solid flesh flung about — each character gets the chance to express their innermost feelings.

When Hamlet uses the play-within-a-play to reveal Cladius’s guilt, for instance, it results in a sequence that captures the king’s psychology with potency. The royals sit and face upstage to watch the play. But when the players’ recreation of Claudius poisoning his brother arrives, Claudius rolls down to the lip of the stage and faces the real-life audience. The grand red curtain — key in many of the show’s images — then closes in front of the rest of the characters, leaving Claudius trapped, alone with his thoughts.

And the show’s most haunting piece of choreography, which provoked sustained mid-show applause on opening night, depicts Ophelia’s drowning. A wide sheet of blue fabric hangs from above while dancers hidden behind the cloth lift Ophelia, creating an image similar to flying. The character’s death is usually announced by Gertrude and not shown; to give it such a heartbreaking rendering emphasizes the violence caused by the title character (Rosencrantz’s and Guildenstern’s murders are shown as well). On his path toward vengeance, Côté’s Hamlet leaves behind a jagged string of bloody carnage. It’s unforgivable — or it would be if it wasn’t so beautiful.