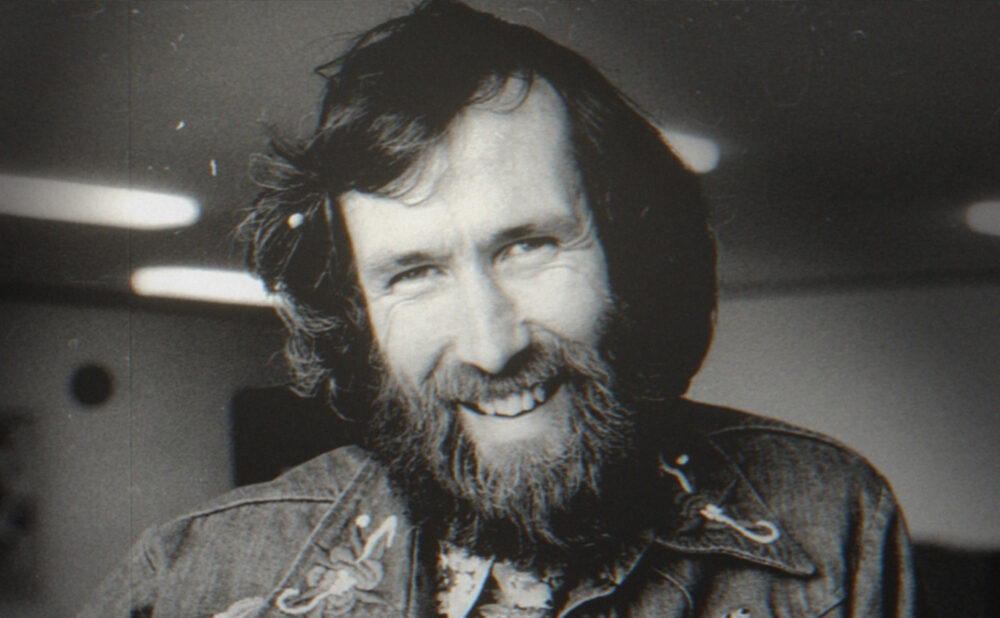

Ron Howard shines a light on Muppet Master Jim Henson

‘Nice guy’ filmmaker celebrates ‘nice guy’ television visionary

Jim Henson Idea Man

What: Movie, 107 mins.

When: Now

Where: Disney +

Genre: Documentary

Rating: NNNN (out of 5)

Why you should watch: Ron Howard’s excellent documentary on the legendary puppeteer Jim Henson is a thoughtful exploration of the artist behind some of the most beloved characters in children’s entertainment from The Muppets and Sesame Street. Henson was as inventive and talented as he was good-natured and introverted. He also longed to be seen as more than “just a kids’ show puppeteer” and struggled with the uneven reception of his film work for “grown-ups.” This warm-hearted documentary features interviews with Henson’s family members as well as archival footage from his famous TV shows and his own film work, including experimental films.

AS SOON AS director Ron Howard joins me on a Zoom call from his hotel room at the Cannes film festival, the wisdom of getting one of the nicest guys in Hollywood, Howard, to make a film about one of nicest guys in television, Muppets creator Jim Henson, is immediately apparent.

Howard is a nice guy as we discuss his most recent project, the documentary Jim Henson: Idea Man, now streaming on Disney+, a fond look at the man who brought us Kermit, Miss Piggy and more. Howard is making as many docs as features these days, and Henson’s family reached out to get him to tell their father’s story. A largely adored man, the family wasn’t afraid to explore Henson’s old-school sexual politics that saw him launch his career and the Muppets with his wife and creative partner, Jane Henson, whom he later squeezed out because he felt she was “unreliable” once she got pregnant, eventually bearing and largely raising their five children.

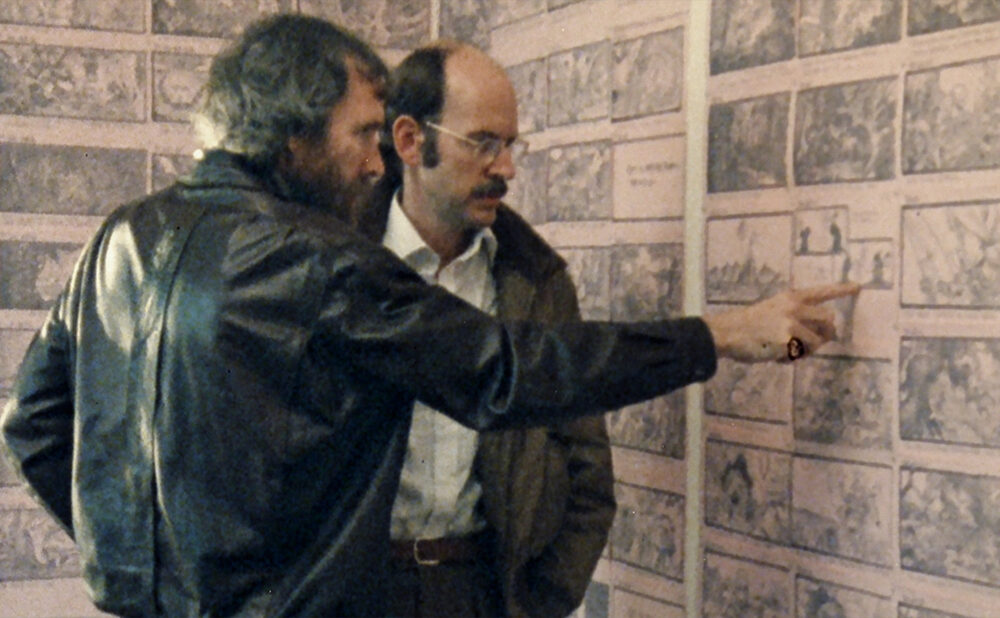

“I was offered the opportunity to explore the doc and talk to the family; I recognized a few things,” says Howard of first meeting the adult Henson children. “One, they had a very mature, emotionally connected but honest understanding of their parents. I felt like they were going to be good, honest interview subjects about their parents. But they also shared this amazing archive of footage that just had us laughing. I knew the film could be entertaining because we could always cut to one of these experimental films or one of these old, crazy commercials that he did or The Muppets, which just reminded me how cutting edge, satirical and hilarious they were.”

The film does dramatically broaden the sense of scope of Henson’s work, including Norman McLaren-esque experimental animations and decidedly adult Muppet puppets smoking and occasionally wielding weapons. An ill-fated attempt to be part of Saturday Night Live’s first few episodes, scripted by the show not Henson, provides some excellent WTF moments. Howard mimics and borrows from the sensibility of Henson’s experimental works in some of the film and its animation.

“Lastly, I just recognized that there was a lot that I didn’t know, so I felt we could make a film that would allow audiences to revisit characters that were beloved to them and yet really understand something about the man behind it all because he didn’t interview much. He didn’t care to do that a lot.

“And I really felt like there was something inspiring and interesting and engrossing about his life to be shared and his relationship with Jane and his kids. So, underneath it, I felt like there was also this very relatable family story.”

The film depicts a man who was constantly working, drifting away from his wife in the process but ultimately bringing many of his children into the family business. Besides, this familial neglect, Henson emerges as a supportive workmate and leader, not prone to dilettantish excess and abuses.

Asked if it’s important to celebrate “gentle heroes,” Howards says,” I think there’s a value in celebrating anybody who achieves on his level; it’s remarkable. And, then to understand the way he could do it and that he broke a lot of conventions. One of them is that he did not have to be a tyrant to get great work done, even in a collaborative medium. “

Howard’s sets are known to be similarly positive work environments.

“He led by example. Everyone said they worked their hardest on his projects, but they were just following his lead. I thought I worked hard, but he would go two days running without stopping. Everybody else, he would say, ‘No, go home and get some rest. I’m just going to stay on this.’ And, it wasn’t drug-fuelled — it was just his own creative adrenaline that drove him to try to maximize these opportunities that came his way. It was a kind of a compulsion of sorts.”

Henson was constantly trying to be more than “the Muppet guy” with TV pilots, major moves and more. He died at only 55 but accomplished a massive amount.

What drove Henson?

“I think it’s a few things,” says Howard. “A couple of which I can relate to, a couple of which I don’t, personally, but I can recognize. I think losing his brother early in life when he was a boy, his older brother meant so much to him. I think he did recognize the fragility of life, and so time was precious to him. And I think he started taking that fairly seriously in his teen years. He was productive, he knew he wanted to get involved in television. He didn’t even care about puppets. It was just a way to get on television because he was excited about that new tech, the new medium. And he didn’t waste any time. He was already acknowledged as kind of an outlier, gifted, as a teenager.”

Henson was in a high school puppet club and was performing Saturday mornings on local Seattle TV while still a student.

“I think he felt like he had to live up to that, if he, in fact, had some gift or some talent, it was important to him to not throw it away, not waste it. In fact, he just didn’t want to waste time. He was playful, he was funny. He could enjoy nature, he could enjoy meditation. It wasn’t about it having to be active or noisy, he just had to be engaged in what he was doing. And it had to have utility; there needed to be a reason, whether that’s hanging out with his kids, trying to be a good family man or working 48 straight hours trying to make a puppet come to life in an exciting, entertaining way.”

Did this compulsion cause his children pain or were they satisfied that what he was doing was important enough to justify the missing time together?

“I think it was a bit of both,” says Howard. “And we try to reflect that in the documentary. Ultimately, they have a lot of respect for the father. They recognize that he was trying to achieve a sort of difficult balance and, at times, they were a little disappointed and dismayed by how much he wanted to work. But by the same token, he included them in what he did. He made himself as accessible as he could and still meet these various deadlines that he kept creating for himself. I think there’s a yin and yang to all of this that we tried to acknowledge in the film, including his marriage to Jane. He would not have emerged as the figure that he did without Jane recognizing his talent, bringing her own talent to the Muppets.

“But at a certain point, too, they started to drift apart in their marriage in a very real way; it wasn’t cruel. It wasn’t harsh, but it was a little sad. And the kids are still a little sad about it when they would talk about it, but they spoke about it with honesty. And I think that there’s an element of our story, which is also a very relatable kind of family story as well. And I recognized that in those early interviews with the Henson offspring and wanted to reflect that in the movie as well.”

Watching Henson struggle to be taken more seriously as he sought to make films “for grownups,” it’s easy to draw parallels with Howard’s own career where he, successfully, evolved from a child actor to a Hollywood A-lister and highly regarded filmmaker.

Asked if he related to Henson’s struggle, Howards says, “There were a number of things that resonated with me in Jim’s journey: his relationship to his work, his family, his sensibilities. But, I like to think I take creative risks; I think all of us do, but he was really an outlier in that regard. You think about the Muppets, you think about Sesame Street, you don’t think that that’s the result of somebody who took a lot of creative risks. But then you look back at those experimental films, you look at the projects that were thought of as disappointments and even failures at the time (including his non-Muppet feature films), you recognize that he was out there on the high wire a good deal.

“So, I think what we have in common is a real love of the medium, an appreciation of audiences and a desire to do good work that will be memorable, that has value to people because it informs, because it entertains — sometimes it does both. And a love of the process, which is part of what creates that restlessness, that desire to get onto the next project because it’s a way of life that’s defining and satisfying. And I think Jim and I shared that.”