Sofia Coppola creates perfect “Elvis” counterpoint with “Priscilla”

Director turns Priscilla Presley memoir into glimpse into “America’s sweetheart’s” inner world

Priscilla

Where: In theatres

What: Movie, 110 mins.

When: Now

Genre: Drama

Rating: NNN (out of 5)

Why you should watch: Sofia Coppola’s sensitive portrayal of Priscilla Presley is a welcome addition to the Elvis myth, giving us a glimpse into the inner world of America’s sweetheart.

FILMGOERS MAY HAVE a lot to be bitter about the last few years (Covid delays, strikes, the seemingly never-ending dominance of superhero films), but we are lucky to have two of the most singular directors of our time, Sofia Coppola and Baz Luhrmann, taking on an iconic American figure, Elvis Presley. It is hard to imagine a more perfect subject for Sofia Coppola than Priscilla Presley, Elvis’s wife. The opening sequence of the film is vintage Coppola: closeup shots of nails being painted coral pink, false eyelashes being applied and white pumps walking across a lush pale carpet. More than any other filmmaker, Coppola is attentive to how her characters interact with their environments, revealing their inner worlds through their surroundings. And despite the careful, beautiful facade, Priscilla’s inner world is in shambles.

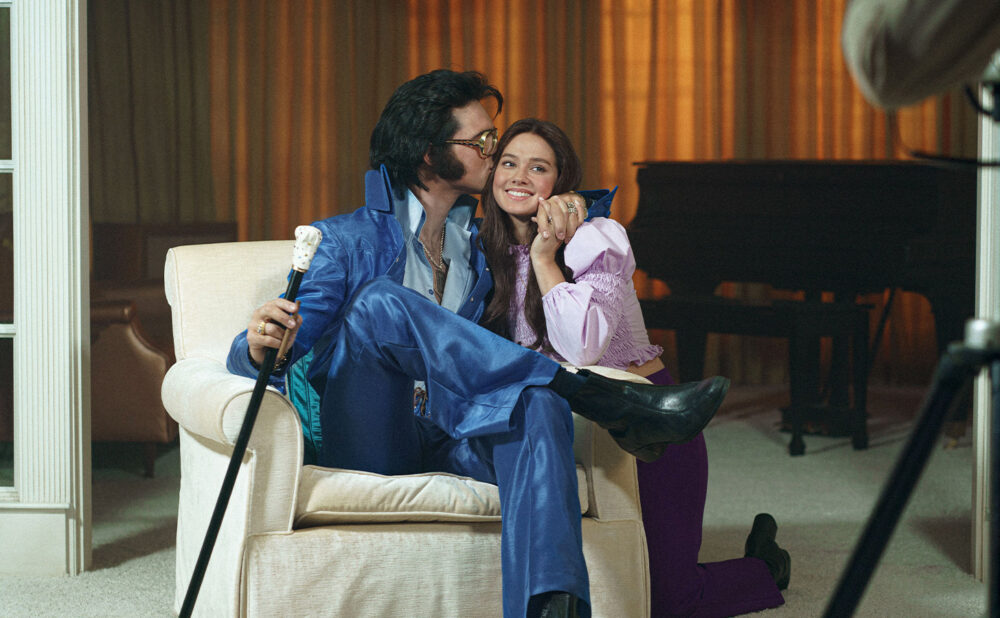

The film opens with Priscilla (played by Cailee Spaeny) at 14-years-old, sitting in a malt shop in Germany (where her father, a U.S. Navy pilot, was stationed). She’s approached by a man who asks her if she’s a fan of Elvis Presley. Of course, she is. She’s later brought to a party where she meets the man himself (played handily by Jacob Elordi) and he takes an immediate liking for her: he says she reminds him of home. Coppola seems eager to strip away any sensationalism from their courtship, the script is sparse, the colour palette is drab and the pacing is slow, all to emphasize that Priscilla is a normal girl, living a comfortable but tedious life. Coppola doesn’t shy away from addressing the age gap between the two (she was 14 and he was 24 when they met), but she doesn’t pass judgment on it either. Their connection is genuine, and their relationship is — for years — chaste. But, we see how their age difference translates, as their relationship develops, into a power imbalance.

The film is based on Priscilla’s 1985 memoir Elvis and Me, and while the film has the approval of the woman herself, Coppola made a few concessions to her own vision (giving Elvis a dark, moody man-cave bedroom). But if there is a certain carefulness to Coppola’s portrayal of Priscilla (especially of the age-gap issue), this is standard of her approach. She’s always been more watchful than analytical, more interested in setting the mood than moralizing. And the mood is, for much of the film’s runtime, quiet, pale and stifling. After Priscilla moves to Graceland (Elvis’s famed house), she’s largely left alone, not allowed to have friends over, take on a part-time job or leave the compound unaccompanied. Elvis is gone for long stretches to shoot films and tour, and she’s left with little to do but study, paint her nails and wait for his call. Coppola paints a clear picture of a woman trapped by her own dream life: married to the most famous, desired man on earth, living in the lap of luxury and deeply lonely. She also doesn’t shy away from Elvis’s flaws: his anger and cruelty, his regressive beliefs about sex and marriage, and his addiction to prescription medication (a habit that Priscilla shares).

Psychologically, Priscilla is more complex and honest than Luhrmann’s Elvis, which only covers their marriage in the most superficial sense. But as the runtime stretched on and we were treated to the same scenes of Priscilla bored in her pastel house, I started to long for Luhrmann’s bombastic, ridiculous fun. The film starts to feel repetitive, stuck on the same wavelength — as if Coppola had run out of ideas part way through. And the scenes of conflict between the couple (which should be the juiciest parts) seem truncated, flashes of violence that fade as soon as they’ve appeared.

Artifice and appearance are essential subjects of Coppola’s films, and here she’s found an incredible muse. Priscilla’s look is truly iconic, beautiful and also false. She’s constantly made up, not for her own pleasure but by Elvis’s insistence (a scene where she tries on clothes for him is eerily reminiscent of Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo). But it frustrates that Coppola seems as invested in Priscilla’s constant perfection as Elvis; Spaeny’s thick eyeliner and false lashes are always immaculate, even first thing in the morning (as someone who has slept in eye makeup, this is simply not plausible). But if Priscilla wakes up extra early to reapply her face, we don’t see it; we aren’t allowed to look behind that facade.

As an immersion into a vision of Priscilla’s life, the film is pitch-perfect; the attention to period detail, the use of music (both timely and anachronistic) and the stillness of the cinematography make a compelling portrait of the tedium of being a housewife to an absent man. But, it’s almost too successful, and I found myself feeling trapped by the film: I had all these pretty things to look at, but I was bored.