Tarragon’s ‘Behind the Moon’ is a patient, moving drama

Writer Anosh Irani’s latest provides nuanced investigation of worker abuse in Canada

What: Behind the Moon

Where: Tarragon Theatre, 30 Bridgman Ave.

When: Now, until Sun., March 19

Highlight: Michelle Tracey’s detailed restaurant set

Rating: NNNN (out of 5)

Why you should go: Director Richard Rose gives the play’s exposition time to breathe, ably setting up for its explosive climax.

Most Canadian theatre is fast. Even in the not-for-profit sector, it’s the convention for plays to move along at least at a jog’s pace.

So what’s incredible about Anosh Irani’s moving new drama Behind the Moon, which opened last week at Tarragon, is the patience with which it builds up its world. Though the play is never boring, director Richard Rose is careful to give its exposition enough time to breathe. This impressive attention to detail allows Behind the Moon’s second act to trampoline into an explosive — and earned — climax.

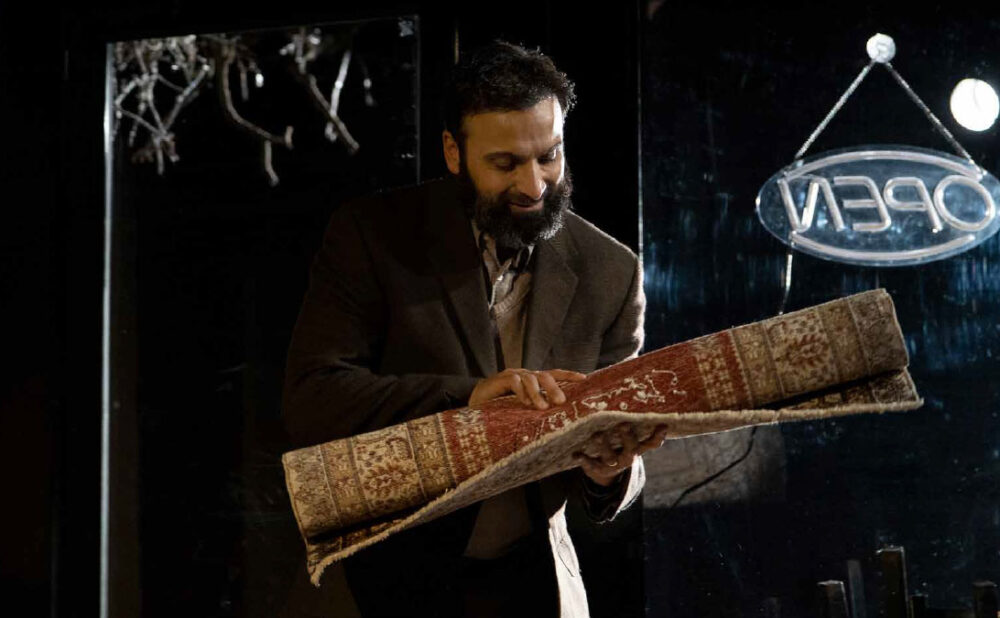

The three-man show is set at the Mughlai Moon, a fictional Toronto Indian restaurant. There, protagonist Ayub (Ali Kazmi) works nights. And mornings. And every time in between.

At first, this only seems to signal that Ayub, who has worked at the Moon for four years, is extremely dedicated to his job. But when his blazer-adorned boss Qadir (Vik Sahay) barrels into the restaurant with a manipulative speech about working hard and bootstrap-pulling, it becomes clear there’s something darker going on.

Qadir’s dominating presence at the Moon is routine, though. What really sets the plot in motion is the appearance of kind-hearted taxi driver Jalal (Husein Madhavji). One night, he bangs on the door past closing and refuses to leave until Ayub lets him have some days-old butter chicken. Nighttime visits like this soon become routine and the men, both immigrants from India, develop a nourishing friendship that they were both desperately in need of.

The first act is carefully attuned naturalism. Michelle Tracey’s realistic set for the Moon includes such details as real food, takeout menus and a thematically important green DineSafe sign. Rose smartly dramatizes Ayub’s labour by having Kazmi perform, over and over, the tasks needed to open and close the restaurant: he mops, scrubs the tile floor, stacks chairs and arranges clattery metal trays of food. We see his exhaustion firsthand.

A glass door to the outside ethereally pierces the stuffiness of the interior. Through it, a warm bath of natural light (designed by Jason Hand) streams in, providing a comforting contrast to the restaurant’s harsh fluorescents. Whenever someone opens it, sound designer Thomas Ryder Payne evocatively conjures the hustle and bustle of the surrounding city. And outside, the restaurant’s electric white sign hauntingly glows while a leafless tree looks pensively on.

This nuanced world-building sets up the second act to lift off into the theatrical stratosphere. In it, magical realism comes charging in to enrich key moments; and one scene includes some bloody violence.

There are even compelling engagements with grief and spirituality. Though Behind the Moon primarily grapples with the frighteningly real issue of immigrant-worker abuse in Canada, metaphysical considerations bubble underneath. By the end of the play, Ayub and Jalal’s friendship has drummed up the power to summon gale-force winds, close the distance between them and their loved ones, and bring reckoning down from above.

Behind the Moon is tender, heartbreaking theatre. Irani chips away — moment by moment, metaphor by metaphor, plate of food by plate of food — until he reaches the molten core of this dangerous situation and the broken people within it.