Walking in Bob Marley’s Trench Town footsteps

Local guides give inside look at reggae’s birthplace.

KINGSTON, Jamaica — A few weeks before Toronto’s recent Caribana festivities, I head to Kingston, Jamaica, to see how an “original” Caribbean Carnival is done. But an unscheduled trip to Bob Marley’s Trench Town streets proves the revelation of the trip.

I’m being given an off-season, off-resort look by locals at the steamy city of Kingston, far from all-inclusive beaches. It includes a truck-top ride in the carnival parade, a visit to Jamaican “Graceland” — the post-success home of Bob Marley on Kingston’s most upscale street — a brief side trip to the unglamourous southern coast (where I finally score some weed from a shack on stilts on a sand bar) and, most profoundly, an afternoon spent walking the dusty, music-drenched streets of Trench Town, statistically the most dangerous place in Jamaica and where I never feel unsafe.

A few days in, I head to the Bob Marley Museum, set up in Marley’s last home, which is still owned by his family and was purchased when the singer “brought the ghetto uptown.” Rolling along Hope Road, we pass the white-walled compound housing Devon House, a sprawling mansion built in 1881 and its grounds, which were once owned by Jamaica’s first Black millionaire, George Steibel. .

The U.S. embassy is along here, and the Governor-General’s mansion is nearby. This was a statement real estate purchase by Marley in his own “movin’ on up” moment, leaving his Trench Town “shantytown” for one of Kingston’s “preferred” addresses. Ironically, Marley came closest to dying violently in this swank setting rather than his childhood “mean streets.”

A gate has to be opened to let us drive into the walled complex. There are walls and fences all over Kingston — around supermarket parking lots, pharmacies, businesses, hotels and homes that can afford them. Billboards on every other block featuring helmet-wearing, rifle-toting tough guys and promises of “live security” suggest the fencing isn’t just decorative.

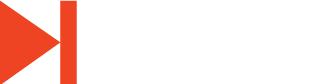

An exuberant statue of a smiling Marley clutching an electric guitar and raising his right hand skyward, attended to by two smaller statues of lions, offers the thrill created by seeing a singer, rather than a general, on a pedestal.

A grand, but not massive, two-storey “colonial” building sits in the centre of the compound with a few other buildings, and I recall newsreel film of Marley frantically playing soccer with his friends on this paved lot. I’ll see locals playing soccer just about anywhere semi-flat, including a late-night, refereed, after-hours game in closed-off, fenced-in asphalt-covered supermarket lot across from my hotel — no sliding tackles here.

Our guide has massive locs and a Bunny Wailer beard and will prove to be laidback about everything except taking pictures: none allowed inside the house. Marley bought this house at the height of his fame and lived here until his death from cancer in 1981. It was a working home and housed his Tough Gong studios, first in the house, later in another building on the site and eventually at a new location downtown, where it remains an active studio today.

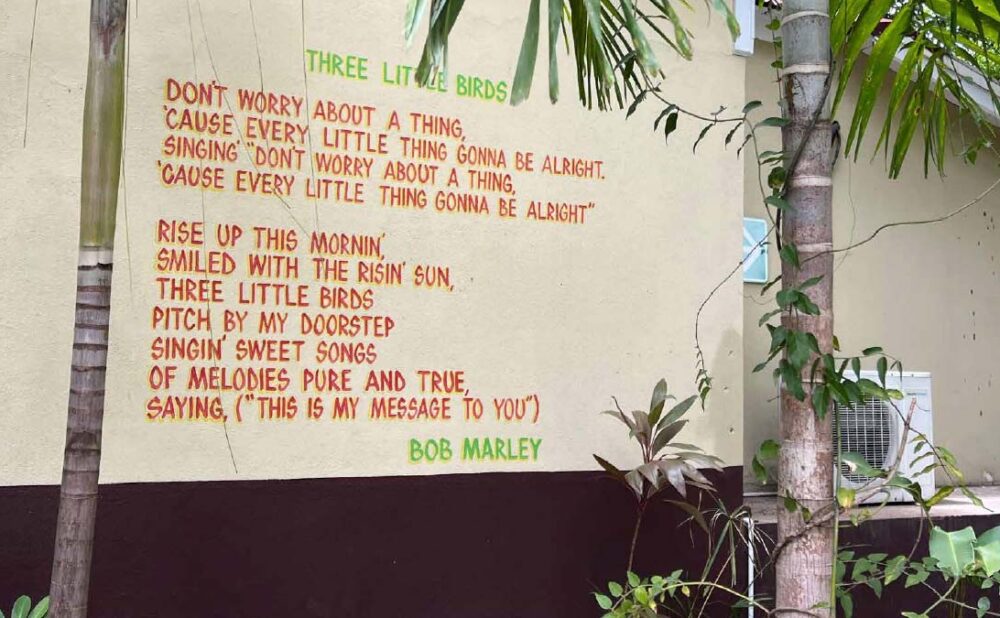

Right off the main entrance to this stately wooden home, we encounter a loaded analogue studio control booth along with two small studios used by Marley, mostly for recording and mixing vocals. His son, Ziggy Marley, still records here occasionally. Marley wrote and recorded many of his later albums here, including Uprising and Exodus. The same way battlefields hold souls even centuries after the last shot is fired, studios hold sounds. And standing in Marley’s preferred vocal room, it’s easy to imagine — even feel — Marley’s presence in this space, trying to get the vocals just right for Three Little Birds or Redemption Song. The room eats sound or maybe absorbs it, sucks it into the acoustic panels and recording devices.

Our guide singing lines from the tracks he mentions helps feed the illusion.

Filing through other rooms in the house, the walls are like vertical scrapbooks with awards, newspaper clippings, gold records and more displayed on every available space.

On the second floor, we are proudly shown a massive, wood floor and walled room taking up one side of the house and featuring slatted-window views that promise a breeze through the breaks in the shutters. We’re told the relatively modest-sized Marley — he was 5’7” — had a massive hammock that almost filled the room, perfect for lounging in, solo or with a friend, “smoking ganja,” listening to the birds and the breeze and maybe writing a song.

We see his bedroom, which looks like he just left it hours ago, complete with a pile of weed ready to roll by his bedside and his “favourite” acoustic guitar resting on his bed. The tour is appropriately reverential: there are no shortage of reasons to celebrate Marley as an artist and as a man, especially his efforts to promote peace both at home and around the world.

But things get a little Pyongyang-y when we return downstairs and into a back kitchen of the house; it’s a little North Korean-esque embellishment as we are told the story of Marley’s surviving an assassination attempt in the days before he was to host a national “Smile Jamaica” unity concert designed to bring literally warring factions of the country’s two main political parties to come together in peace during the incredibly violent ’70s in Jamaica.

Details of what happened back on Dec. 3, 1976, days before the planned concert, vary wildly. But the big concrete wall currently surrounding the home hadn’t been built yet, and “seven or eight” gunmen easily breached the compound, firing randomly as they searched for Marley. Marley and two others were in the kitchen when a gunman burst in and unleashed shots at the trio. Our guide insists that Marley, being “incredibly fit,” was able to bend, twist and dodge the hail of bullets meant for him and that would kill his companion, Don Taylor.

(Rita Marley’s locs are said to have stopped a bullet penetrating her skull when she was shot in the head while sheltering in another part of the property.)

Bullet holes the size of quarters remain in the kitchen wall and, though he did take a slug in the arm, Marley was able to perform his Smile Jamaica concert, himself smiling as he brought the two battling candidates for prime minister together, at least for a moment, to share a stage with him.

This iconic scene in front of thousands at the National Stadium is shown (along with many others) in a satisfying film screened at the end of the tour, in a building adjacent to the house that once housed Tough Gong.

As the tour “exits through the gift shop,” I’m not tempted by stacks of stuff featuring the ubiquitous Marley, his bootlegged image featured on beach towels, T-shirts, coffee cups and bandanas the world over.

Hungry for a more authentic way to wrap up this day, I want to see where Marley is from rather than where he ended up. While his childhood home of Nine Mile is hours away, the Trench Town streets that shaped him from his adolescence through early adulthood are a few miles — and a world — away.

Where is “that government yard in Trench Town”?

I ask if it’s possible to see that “government yard in Trench Town” and am assured the answer is “Yes.”

As we descend from this upscale neighbourhood, towards downtown Kingston and the port next door to Trench Town, the concrete walls become less white and the stuff on top of the fences gets a little sharper and more menacing. While concrete limits the architectural creativity, in a country where killer hurricanes are routine , solid concrete walls and relatively small windows stand the best chance against fatal winds.

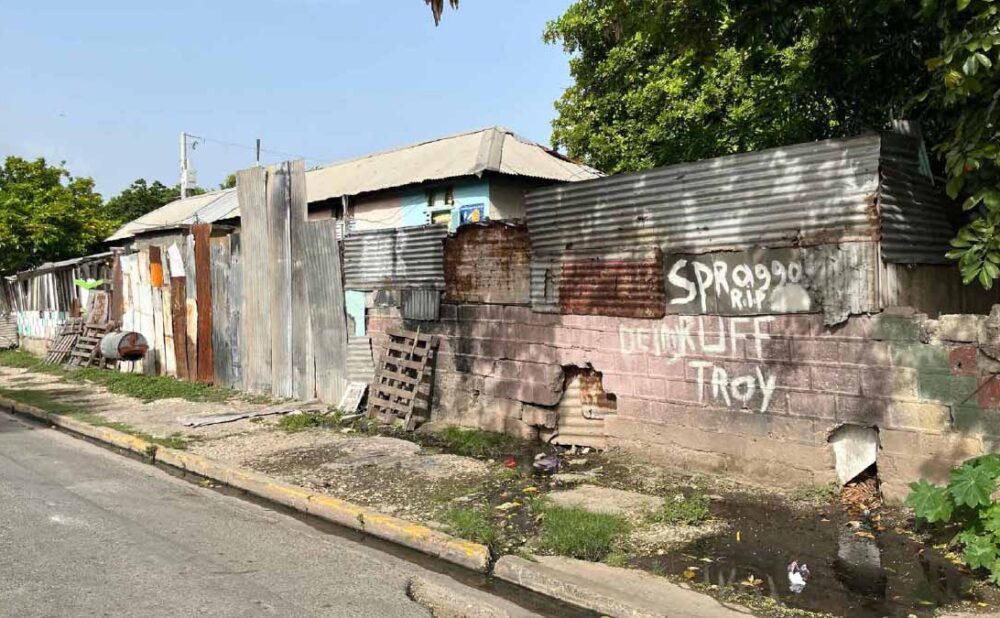

Concrete and brick are definitely a matter of class, and lower-income residents are limited to wooden shacks with corrugated zinc roofs. As concrete increasingly gives way to wood as the dominant home material, we are approaching the approximately 12 blocks known as Trench Town. While trenches for water run-off do indeed fill the area, Trench Town got its name because the land was originally owned by an Irish settler named Daniel Trench, who grazed cattle here before his family abandoned it in the late 19th century. The deserted land eventually became home to a squatters’ village and, in the ’50s, the colonial government created some basic, assisted housing.

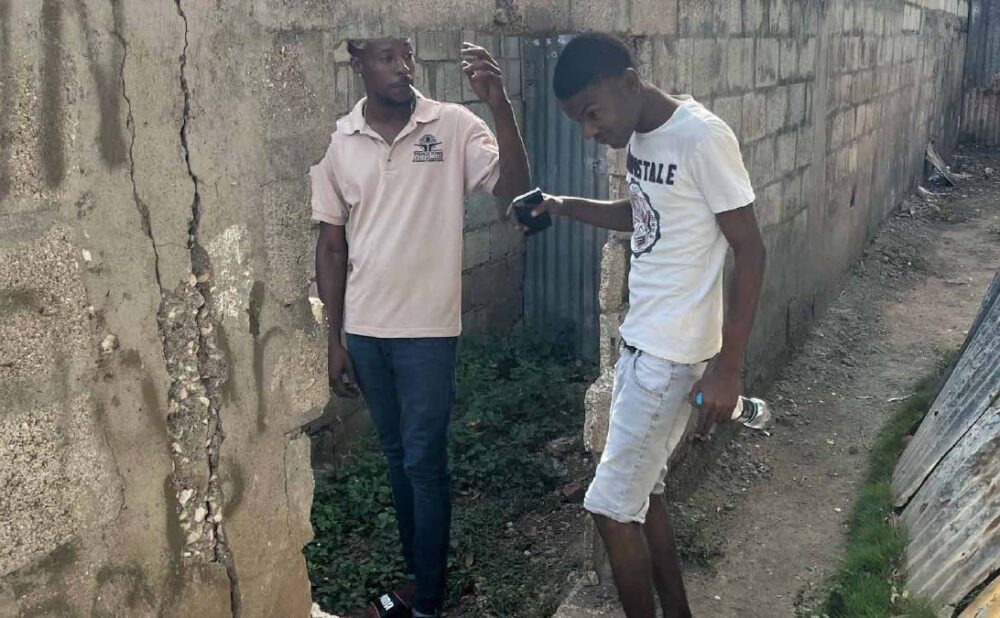

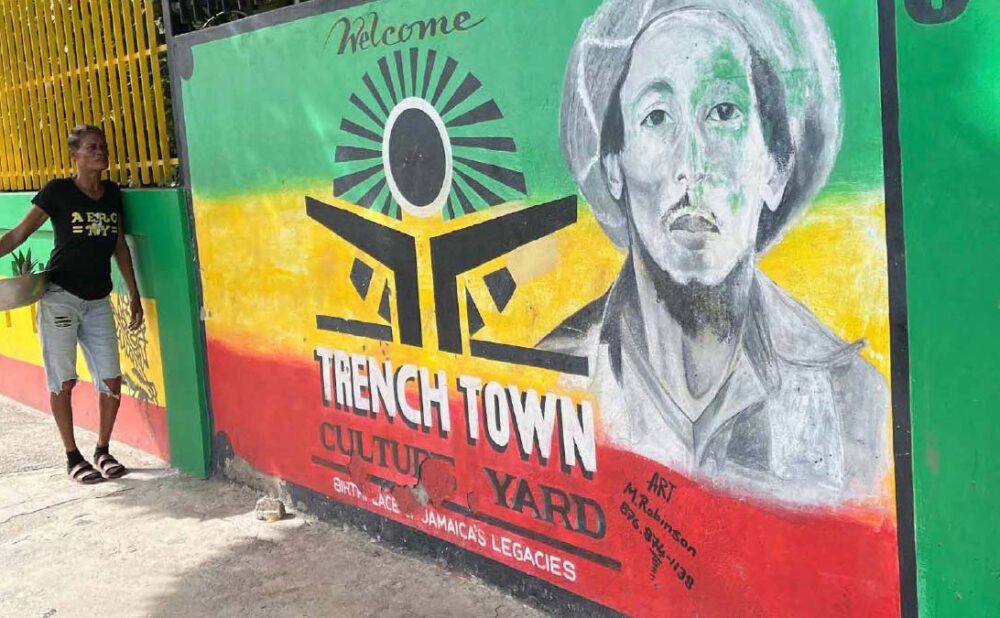

We arrive in front of another wall and gate, this one brightly painted in green, red and yellow, with a fading portrait of Marley and paint-peeling words that declare “Welcome Trench Town Culture Yard Birthplace Jamaica’s Legacies.” I think the word “of” has chipped away, but I get the point. My tour ticket has been pre-purchased and my instruction is to connect with my guide inside the yard walls with the promise that Marley’s early Trench Town home will be revealed.

The Trench Town Culture Yard Museum is owned and operated by neighbourhood residents with the goal of providing a more authentic understanding of Bob Marley and his roots as well as the roots of reggae, all in the context of past and present Trench Town.

There’s a distinctly mellow vibe as I survey a couple of low-slung buildings in a treed and shaded courtyard, concrete benches offering respite to a handful of young dudes all with left hands filled with weed as their right hands try to break it up for rolling. A radio blasts music, seemingly ignored, and the broadcast is interrupted for a Big Brother-style message from the Jamaican prime minister, who implores all who are listening to resist the urge to spread misinformation and panic among the populace.

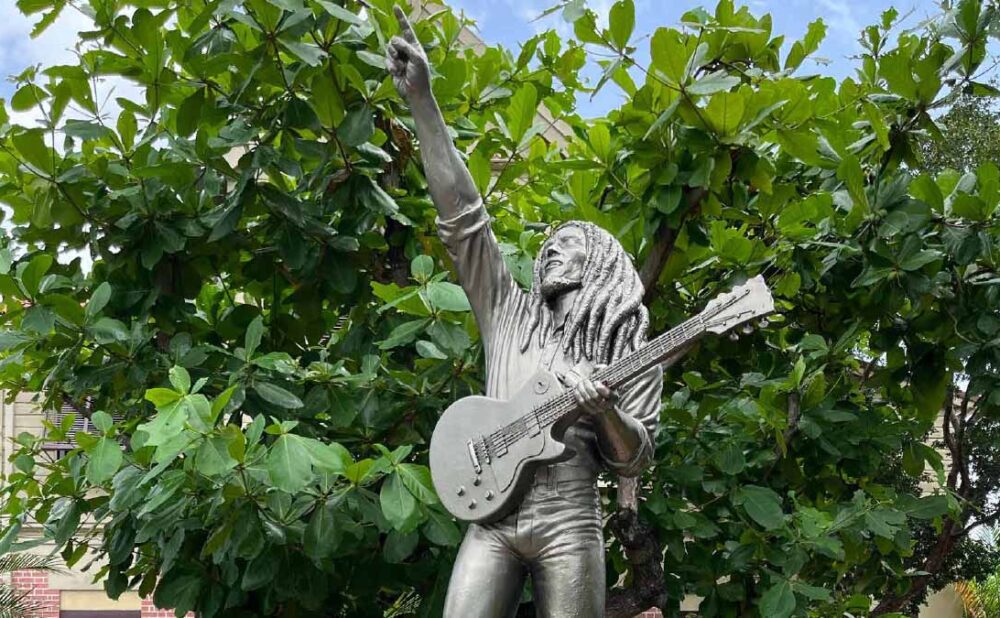

Nobody seems too concerned by his words and, eventually, a young man in his mid 20s in a collared pink T-shirt, with a small “Trench Town Culture Yard” logo on the chest, makes his way to me and says, “With you in a minute.”

He flits among the seated scattered among the yard and then returns to me, jangling keys with the universal “let’s go” body language pointing me towards a path between the buildings. We emerge in a pebbled courtyard that is surrounded by a U-shape of three, small, low-rise buildings.

“Is this where he lived?”

“This is that ‘government yard in Trench Town’, I’ll show you,” he says. I eventually learn my guide’s name is Shaquille Lewin, but like everyone in Trench Town, I will call him Kash “with a K.”

Eight doors, each representing a family’s home, line each side of the U that creates the yard, and Kash points me towards one that he unlocks, eyes looking everywhere but the door before opening it to reveal a tiny room, about 15-feet wide and about 10-feet deep. He lets me in before purposefully disappearing as I look around puzzled. He reappears just as I start to take a picture. “No pictures inside any building,” Kash quietly explains, more urgency in his look than his words.

This block of homes was created in the ’50s as part of an “urban renewal” project that saw two other, higher, levels of government housing also created in Trench Town. The other homes have more space and higher rents. Marley, his mom and siblings moved into one of these bare, cell-like rooms when he was nine. His Mom would later move to a larger unit elsewhere in Trench Town with Bunny Wailer’s father — Bob and Bunny are rumoured to be half-brothers — and a teenaged Marley would eventually get his own unit where he started his own family before the big move uptown. It seems almost impossible that an entire family would be able to sleep in the space all at once.

The rooms have power but no kitchen or plumbing; two common toilets and cooking areas at the edge of the yard were shared among all residents. All the “sharing” in Marley songs, from a “single bed” to “cornmeal porridge” makes more sense upon viewing the smaller living spaces and larger, common community areas of Trench Town. Hard to imagine the doors around this yard ever being closed as families spill out into each other’s lives, the kind of mayhem that can make parents stressed but provides endless opportunities for kids to hang out with pals and family.

The “poor but proud” trope has served white male entitlement and guilt for centuries, but as Kash shares Trench Town tales, stories of his neighbourhood — especially its rich musical history — he is indeed proud, and I am reminded how easy it is just see “a slum” where the residents see it as home..

“My grandfather was Bent Dowe, lead singer from the Melodians,” Kash tells me with — yes — pride. If your knowledge of reggae music started with the Jimmy Cliff film, The Harder They Come, you’ll know Kash’s grandad from his lead vocals on the excellent track, Rivers of Babylon.

While low key — he is pretty high — Kash is focused on sharing the Trench Town story, offering whispered, deep details about zoning decisions and almost demanding I take notes as if this will count on my final grade.

He unlocks and locks other rooms around the yard. He shows me where Mortimer Planno (Marley’s mentor in all things Rastafarian) lived, and it is easy to imagine Marley sitting by Planno’s bedside as the older man shares the teachings of Jah with his young charge.

Time for the real tour I am told

“This is the one Bob moved into on his own, where he started his family,” says Kash opening another door to reveal a tiny room with a single bed that fills about half of the space.

“You know that song, Is This Love?” and he sings, “’With a roof right over our heads, we’ll share the shelter, of my single bed, we’ll share the same room.’ This is that room,” and he points at the tiny bed. “Not the same bed, but the same room. Ziggy Marley was conceived here, born here — no hospitals for that — and raised here.”

I was lucky enough to see Marley play live at University of Toronto’s Convocation Hall in 1976, truly one of the greatest, most unforgettable performances I have ever witnessed, so it feels like a privilege walking sacred ground to retrace the singer’s steps. I contemplate each of Kash’s Trench Town details as if regarding holy objects, and as he shows me a sports courtyard, sensing my appetite for information, he says, “Too bad you’re not taking the bigger tour; then we can really see Trench Town.”

Hustle or a home run, I wonder? I’m eager to say yes but puzzle over what I’m agreeing to. If I’d taken a closer look at the Trench Town Culture Yards Museum price list — I never did see it — I would have noticed a “walking tour” option.

“Yes,” I say enthusiastically, and we return to the entrance area’s somnolent scene while Kash has a few quick conversations and grabs a huge handful of weed from one of the silent seated. As we head out the gate and start towards — well, I’m not sure where — we are joined by another, smiling younger person. I’ll eventually learn this teenager’s name, Javauni Walker, Ja to his friends, but right now I’m tamping down my usually suspicious travel instincts and surrendering myself to whatever comes next.

Just as we head to full stride, I hesitate — and it’s noted. I have an over-the-shoulder fanny pack and a goofy, green Saskatchewan Roughriders ball cap — it’s fucking hot! — and I consider leaving it with my host(and driver) before heading off, in a hopeless effort to look less like a tourist.

Ja sees my hesitation and says, “Don’t worry, you won’t be robbed.” I’m horrified, already wrestling with tons of liberal guilt and a desire to be respectful heading onto their home turf.

“No, not worried about being robbed, just wanted to look less like a tourist, but I guess that fight is lost,” I say laughing.

“Everyone knows you’re a tourist if you’re with me,” says Kash confidently and reassuringly. “Anyway, we wear those bags too, they’re cool.”

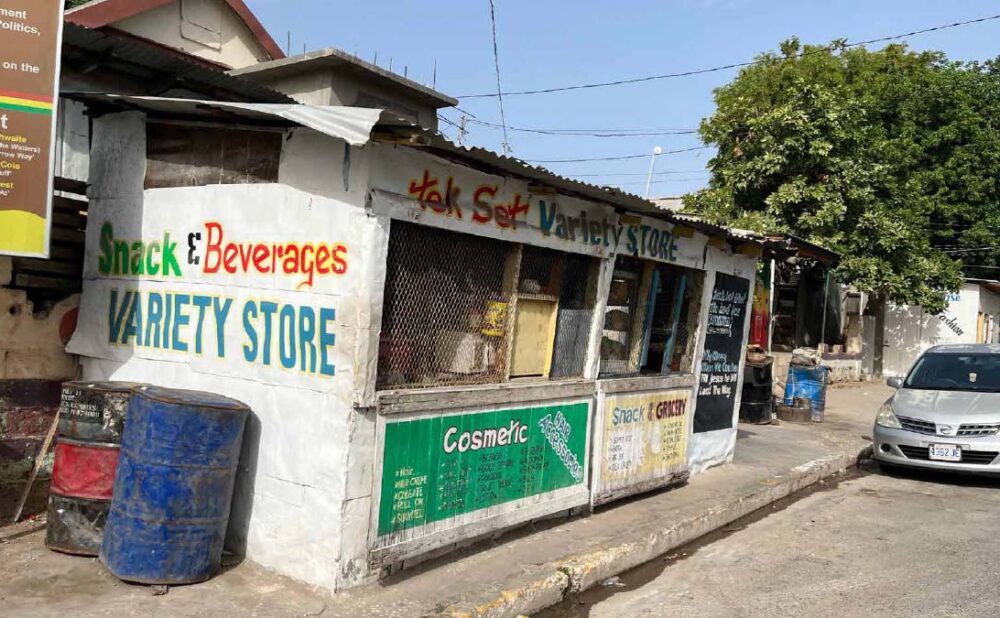

The streets are wide and lined with corrugated, zinc-roofed shacks supported by rescued wood — or sometimes brick, cinder blocks or concrete and plaster — skillfully patched together like an architectural collage.

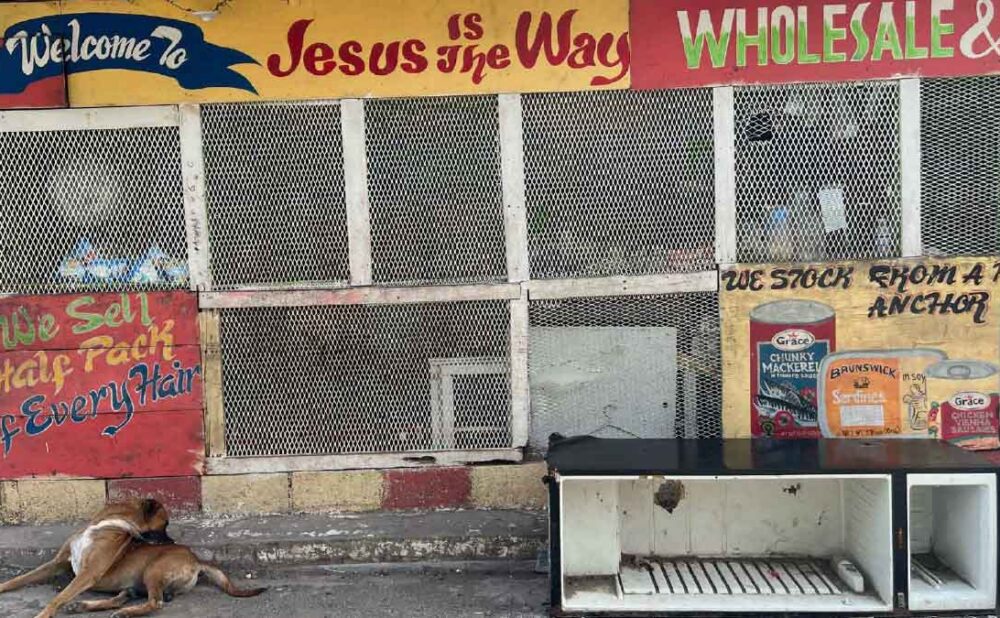

“Want some water?” asks Ja before disappearing into a shack that looks abandoned except for the three people sitting on benches outside. After a steady visual diet of white-washed concrete in posher Kingston neighbourhoods, the found building materials, makeshift structures and fences, and sometimes colourfully painted homes are a veritable peacock palette.

My eyes are feasting on the revelatory scenes I am consuming, but I am conscious that I am being brought into someone’s “home” and deeply desire to be respectful in my fascination. Don’t want to come across like “Your poverty sure looks cool.”

A mural along a wall as we head to the top of First Street, one of a dozen or so long main streets here, declares “Welcome to Trench Town the Home of Reggae Muzik,” with portraits of Marley, Peter Tosh, Marcus Garvey, Martin Luther King, Haile Selassie and more.

Ja and Kash tease me about how quickly I snap my pictures, I’m eager to be subtle but Kash wants me to be sure I have good shots of all the historical markers, especially the ones at the top of each street that proudly list the reggae superstars that once lived — or still live — there. Bob Marley, Bunny Wailer and Peter Tosh are among those listed having lived on First Street.

“Just don’t take pictures of people without asking,” I’m told, and I have every intention of complying.

One side of the street is densely packed with only wood-and-metal shacks while the other side has sturdier structures in the mix.

Peter Tosh’s family never moved from this side

“Peter Tosh’s family lived down there,” says Kash pointing at the dilapidated homes. “They never got out of the shanties until he was a star.” From the three levels of government housing, of which Marley lived in the “lowest,” to preferred streets, there is a hierarchy lurking in Trench Town, too. I’m shown the two-storey structure where Marley’s mum lived with Bunny Wailer’s dad, the building now charred and unrepaired after a fire ripped through it.

It seems everyone we pass knows Kash and Ja, and literally everyone has a handful of weed in their left hand, including Kash, as they twist and crush the incredibly sticky Jamaican bud so it can be rolled. Like an herbal fidget spinner — or a rosary — constantly processing one’s weed seems to be a relaxing diversion or an essential task in preparing the gummy ganja.

We pass someone who seems a little burnt out as they muster only the most basic greeting for Kash despite his enthusiastic “Hello.”

Kash apologizes for his pal, noting, “He was up late last night playing at a party; he’s got another one tonight”.

“Was it a carnival event?” I ask naively.

“Carnival?” Kash snorts with some incredulity. “There’s a party every night in Trench Town.” He explains the parties feature DJs and live performers with massive sound systems. And lots of sexy dancing.

“We dance rub-a-dub style, and you can see why it’s easy to make babies in Trench Town.”

As if on cue, two young women make their way towards us, and Kash and Ja exchange flirtatious smiles and comments with them.

“See you at midnight, Anna,” Kash declares confidently, almost insistently, to one of the women. She gives him an “If you’re lucky” look and walks on, smiling.

With windows shuttered to beat the heat, it’s hard to tell what’s operating and what is abandoned. And while music isn’t everywhere, there’s plenty. And when it’s heard, it’s loud and very clear, coming from excellent, unseen and, I suspect, massive speakers. As Little Nas X and Jack Harlow blast magnificently from a concealed system, I remark, “Not just reggae in Trench Town.”

“Not just reggae,” they both assure me, insisting they listen to everything here.

As we linger, reading the celebrated names at the top of another street, an older man wearing the only mask I will see in Trench Town comes purposefully towards us and starts telling me what I should insist my guides show me. He then gets harder for me to understand as a few choice curse words I’ve heard Jamaican friends use come through. It’s not hostile, just insistent.

As he moves on, Kash chuckles and says, “He was speaking patois, he was playing with you. You know patois?”

I dig deep into the vault and mutter, “bloodclaat” to approving grins.

We come to a fenced-off building that looks abandoned, and Kash purposefully unhooks an unlocked lock that connects a chain in front of the doors.

“This is the community centre. Everyone uses it,” Kash says. We head in and find a recording session just wrapping up in a decent studio and control booth. I’m told all “the legends” have taken advantage of this space to record.

It’s the JaMIN Recording studio, set up under the Jamaican Violence Prevention Peace and Sustainable Development Programme, “geared toward developing alternative livelihoods for residents of tough inner-city communities.”

After listening to some play back — sounds great — we head back to the streets. As we emerge, both Kash and Ja nonchalantly light the joints they have managed to roll while we walk. While I don’t have their walking-and-rolling skills, I wisely pocketed one of my own messy pre-rolls before coming and light mine up to approving and somewhat surprised smiles.

“Old school,” they both agree referring to my joint rolling style.

“Where’d you get it?” I’m asked.

I explain that I haven’t figured out where to get weed legally in Jamaica where cannabis is de-criminalized but scenes like the ubiquitous weed stores of Canada have not reached these shores.

“Got mine from a guy I met on a shack on a sand bar that I reached in a fishing boat when I made a side trip out of the city to the south shore,” I tell them.

“Government weed is no good anyway; we never buy it,” they both insist. “Makes you hungry. It’s not healthy,” says Kash, and they both agree the Trench Town supply is far superior. Personally spoiled by the variety and fragrance of Canadian legal cannabis, I find the Jamaican supply acrid and gummy, the way I remember it, but just fine for the rest of the tour.

It’s easy to disappear in Trench Town

We now forsake the relatively wide roads of Trench Town and make our way through back alleys, broken fences and increasingly narrowing paths.

“It would be easy to disappear down these,” I say. “Hard to be found if you didn’t want to be.”

Ja assures me I’m right with a sly smile and I later learn these seemingly random alleys were created at the height of the ’70s’ violence as escape routes.

We emerge at the edge of a field of baked earth surrounded by homes and buildings.

“Sundays this place is packed for football; everyone comes and, in Trench Town, everyone plays,” Kash assures me, and both men smile, clearly recalling great weekends spent here. Presently, a goat roams the pitch; he’s not a mascot but he might be somebody’s dinner.

A few streets over, we come upon another soccer field, this one is fenced and has grass. A bunch of kids are being dutifully run through drills by their coach, and Ja and Kash shout wise cracks at players they know.

Back at the culture yard, I say goodbye to my guides. As my host starts the drive through Trench Town and back up town he says, “You know, statistically, you’ve just spent the afternoon in the most dangerous place in Jamaica. Did you feel unsafe?”

“Never,” I reply.

“It’s the same with me. You saw kids playing. I never feel unsafe here. the violence is gang on gang. But look over there,” and he points as we drive past a sand-bagged Jamaican Army installation on a street corner as armed soldiers sit and watch.

Later that night, I am eager to get to a club, ideally the legendary Dub Club up on a hill overlooking the city. But it’s Tuesday, and the club is closed. In fact, I’m told Tuesday is a pretty quiet night in Kingston.

We end up staying uptown and going to the relatively swank Janga’s Soundbar, which my host describes as “suburban.” There’s a great DJ, and Tuesday or not, the upper-middle-class crew in their 30s and 40s who pour into the venue are slickly dressed for a night out.

I perk up when it is explained that it’s okay to smoke cannabis in the club. “You just have to sit in the smoking area.” The “smoking area” is not a vented, closed-off space but a comfy spot in the middle of the room with a coffee table, couches and a fan. I sit across from a couple who look like they could be somebody’s mom and dad, and while we all sink back into the cushions and light up, my thoughts go back to Trench Town and the FOMO eats at me. Just how big is that party happening right now and did Kash make his midnight meeting, or was he left to find a new rub-a-dub dance partner?